Today — January 6 — is the Feast of Epiphany. I didn’t grow up in a tradition that followed the church calendar, so I was an adult when I learned, for example, that Advent is not the same thing as Christmas, and it was several years later that I learned about Epiphany (four weeks/Sundays of Advent lead up to twelve days of Christmas, followed by the Feast of Epiphany on January 6).1

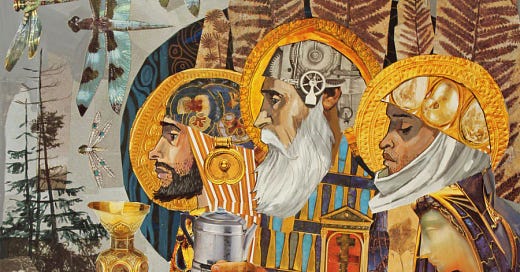

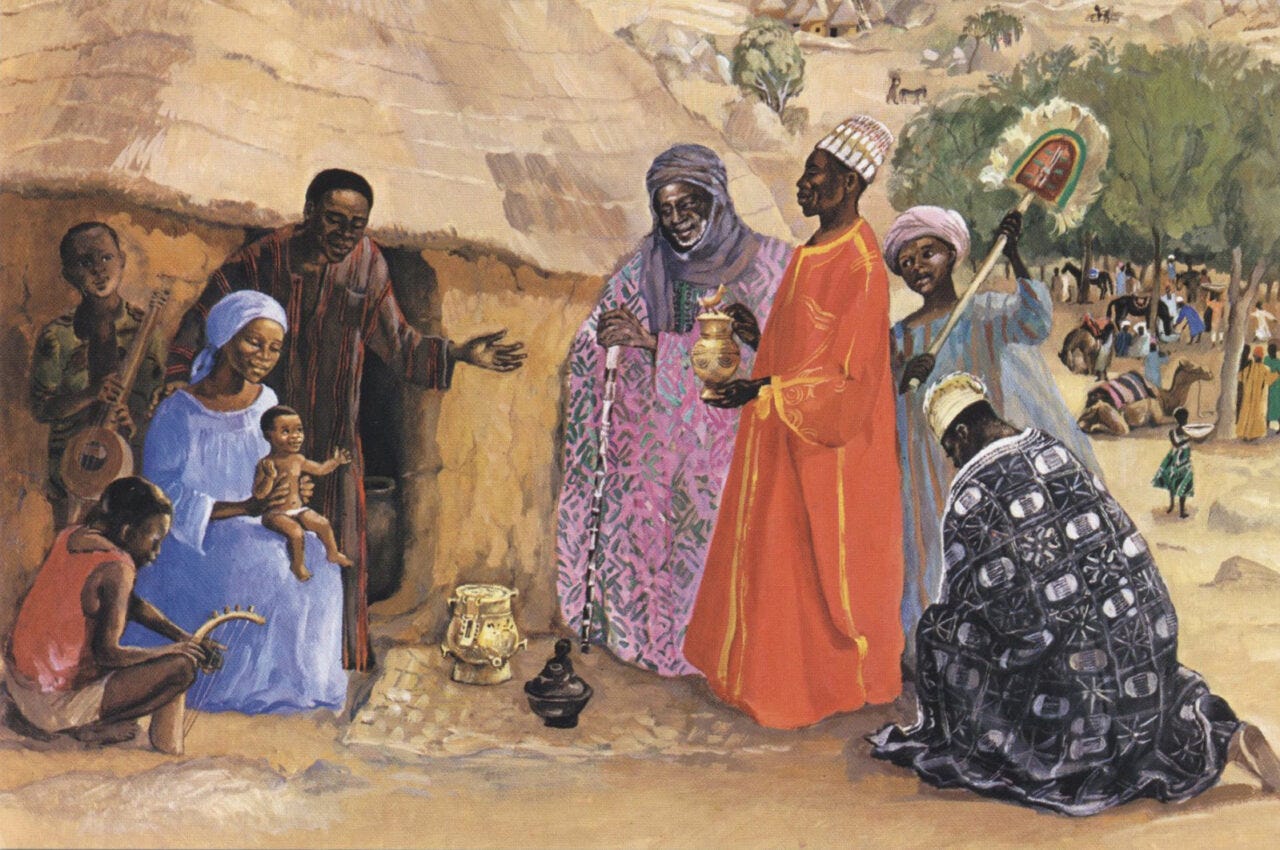

Epiphany focuses on Matthew 2, and there’s a lot going on in this chapter. First, “Magi from the East” travel to Jerusalem and ask King Herod where they can find the “one who has been born King of the Jews,” since they saw his star in the skies and want to worship him. The expert consensus points them to Bethlehem, and Herod asks the Magi to make sure they report back to him after they find the child. They rejoice when they find Jesus with Mary, and they worship him and give him lavish gifts.

But then it turns out both the Magi and Joseph are warned about Herod’s violent intentions in dreams, so the Magi skip town by a different road, and Joseph takes Mary and Jesus and flees to Egypt. When Herod realizes he’d been tricked, he has all the children two and under in Bethlehem slaughtered. Eventually, Joseph learns in another dream when Herod has died, and the young family is able to return, though they make their home in Nazareth to avoid Herod’s son Archelaus.

These are stories that have been told and retold for centuries, and though there may be a few misconceptions to clear up (Jesus was probably a toddler at this point—not an infant like in Luke’s account, it also never says there were three wise men—it was probably a sizable caravan), they invite deep reflection.2 Here in this first record of Jesus receiving worship from Gentiles, people often reflect on themes of following God’s light, the inclusion of outsiders, experiencing generosity with Jesus, resisting violent leaders, and unexpected journeys when you can’t go back home the way you came.

But this year my attention was drawn to the vulnerability of the victims of violence. In this story, Jesus is a toddler who is a refugee — on the run with his family because of the murderous tyranny of an insecure king. That king’s violent greed was threatened by what he heard from wise foreigners who discerned God’s movements in the heavens (signalling the end of that king’s power), and he slaughtered all the toddlers and infants in a whole village out of greed and fear.

This chapter begins and ends with dangerous kings. Insecure kings are really dangerous.3

On the calendar, this story comes after Advent and Christmas, when we’ve just spent six weeks reflecting on how Jesus is Emmanuel—God With Us. Matthew’s contrast is pretty explicit in this chapter—when God arrives to live among humans, poor refugees and wise outsiders are centered in the story as the ones who participate in what God is up to, while those with institutional power violently miss the point.

Believe it or not, the first time I was asked to teach about Epiphany—January 6—was 2021. The juxtaposition of the violence of that day with the witness of Epiphany was awful.

Now, Matthew is a masterful writer. Often called the most Jewish gospel, his writing is layered with references to the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament). Chapter 2 is no exception— it is thick with quotes and allusions.4 Remember, quoting prophecies is more than checking predictions off a list; when Jesus “fulfills” prophecy, the writer is showing how he fills and overflows all the expectations of their story as a people.

But it’s bigger than that. Matthew is casting Jesus as a new Moses, which also means that what Matthew is saying without saying it is that Herod is cast as Pharaoh—the powerful and insecure king who murdered children in Exodus 1. This reenactment of the violence of Pharaoh in Matthew 2.16-18 is often called “The Massacre of the Infants” or the “Slaughter of the Innocents:”

“When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the Magi, he was infuriated, and sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old and under, according to the time that he had learned from the Magi. Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah:

‘A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation; Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’ ”

Reading this section makes me think about how much where, and when, and how we grow up affects our imaginations.

What I mean is this: I grew up in a wealthy country, but spending a lot of my adult years in a very poor country has changed how I hear these verses. For most of my life, the point of this text was “Wow, look how God rescued Jesus and Joseph and Mary by warning them ahead of time!” But it was only after living in a country that was still recovering from recent wars, with a high infant mortality rate, among people who are invisible or unimportant on the world stage, that I thought about the other mothers—and wondered why didn’t God warn them ahead of time too?

The grief is intense in these verses, and we don’t get an answer to that troubling question.

Now the quotation in that section is from Jeremiah 31, which is kind of unusual, because it’s a sad verse within a chapter that’s all about hope. But Jeremiah 31 is also an unusual chapter, because it’s a chapter of hope within a book of grief. That hopeful chapter about restoration and a New Covenant is located in the larger context of Jeremiah, who as a whole bears witness to devastation and trauma. Matthew is aware of all the layers he’s inviting us into.

So I’d been holding these questions for awhile (What about the murder of these other children? What about the other mothers? How does God hear their lament?) when I was relieved to find a book on Jeremiah that brings in the perspective of the recent decades of trauma studies.5

Side Note: I have known a couple Bible professors who’ve turned up their noses to anything “therapeutic” because it wasn’t part of their inherited Biblical Studies training—you know, anything new must be a fad. Which is, of course, disappointing—I think trauma is really old. The perspectives and resources that have been excluded from seminaries run predominantly by white European and American males are not new, and they’re not passing trends.6

We would be foolish to assume that the characters we’re reading about—in Exodus 1, in Jeremiah, in Matthew 2—didn’t experience real trauma after the violent events described in those texts, or that their trauma didn’t affect the transmission of their testimony. And even more recently I encountered the book Trauma and Grace: Theology in a Ruptured World by Serene Jones, who is President of Union Theological Seminary in New York. One of her chapters enters into the questions of trauma—right here with this passage in Matthew 2.

In that chapter she asks: what would Mary the mother of Jesus say to one of the wailing mothers from Bethlehem who didn’t get to escape to safety with her small child?

She describes how unresolved, unhealed trauma affects people: limiting or stifling their sense of agency, time, voice, imagination, and vocation. But then she goes on to ask what would Mary the mother of Jesus and another mother from Bethlehem—represented here by Rachel—what would they say to each other if they met in Jerusalem on a Friday 30 years later as Jesus hangs nearby on a cross, murdered by insecure religious and political leaders conspiring together?

What would it be like for them to meet at these very different moments in their stories? How might they witness to each other’s pain and horrifying grief? Would they hold onto each other? How long would they cry?

And then—how would they each process the unbelievable news of Jesus’ resurrection on the third day after that?

We are the body of Christ—we hold together memories of crucifixion and resurrection, and we hold onto each other. We bear witness both to tyranny and terrible loss and also to rescue and to the unbelievable hope of New Creation, and somehow in between we worship.

We are connected both to Mary and Joseph and the other mothers and to these unnamed magi in the ancient people of God, and we bear witness to and participate in their stories:

Sometimes we see light where others see darkness.

Sometimes we escape violence.

Sometimes we don’t escape and we suffer terrible loss.

Sometimes we give away our wealth to generously finance someone else's deliverance.

Sometimes we can’t go home by the way we came and we have to courageously and creatively figure out how to build a new life in an unexpected place.

And all along the way in between loss and hope we struggle to find a way to worship.

Epiphany reminds us that worship invites us to imagine the larger New Creation story that is outside the scope of Pharaoh’s and Herod’s small imaginations.

Epiphany reminds us that worship trains us to give our adoration and allegiance only to our Faithful Creator. Pharaoh and Herod will never love you back.

Epiphany reminds us that worship is an act of creative defiance, because we are rejecting the violent reign of all the Herods and Pharaohs around us.

Epiphany reminds us that we worship with others; we rehearse our resistance to Pharaoh and Herod alongside all those who come before us.

O come all ye faithful. O come let us adore him, Christ the Lord.

© Ladye Rachel Howell. All Rights Reserved.

The Feast of Epiphany was declared official at the Council of Tours in 567, though many earlier sources mention it. Different branches of the church have variations on traditional practices for Epiphany (such as also focusing on the baptism of Jesus or different dates based on the Gregorian calendar).

Scholars acknowledge that there is no extrabiblical (historical or archaeological) evidence that attests Herod’s slaughter of infants in Bethlehem, but we do know a lot of his violent actions. Craig Keener describes how among all the historical references to Herod’s murderous cruelty that are recorded—he killed (or arranged to have killed) multiple family members by horrible means (drowning, strangling, cudgeling)—so it’s not difficult to imagine other instances happening that weren’t recorded by outside historians, especially if Bethlehem were a small village at the time. Craig S. Keener, Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, p.110-11.

The Herod in this story is “Herod the Great,” who is different from his sons Archelaus (end of Matthew 2) and Herod Antipas (who shows up later in different gospel accounts), and also different from his grandson Herod Agrippa 1 (mostly in Acts) and his great-grandson Herod Agrippa 2 (closer to the end of Acts). His family was favored as puppet kings installed by Rome (who was really in charge), and Herod wasn’t strictly Jewish since his father was Idumean (Edomite), but his family converted, and he also married into the Hasmonean dynasty and gained status there.

In verse 6 Micah 5.2 and 2 Samuel 5.2 are spliced together. When wise foreigners bring the wealth of nations as tribute to the child Jesus, we can hear the poetry of Isaiah 60 humming in the background (which also makes me think of the commission at the end of Matthew— Jesus is already following his own commission by making disciples of all nations). The flight to Egypt that is financed by the wealthy donations of outsiders also alludes to Exodus 12. “Out of Egypt I have called my son”, is a direct quote from Hosea 11.1. The Nazareth/Nazorean reference has multiple possible interpretations; see Keener, p. 112-15.

Jeremiah: Pain and Promise by Kathleen M. O’Connor.

See The Next Evangelicalism: Freeing the Church from Western Cultural Captivity by Soong-Chan Rah, Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope by Esau McCaulley, An Introduction to Womanist Biblical Interpretation by Nyasha Junior, If God Still Breathes, Why Can't I?: Black Lives Matter and Biblical Authority by Angela Parker, The Hermeneutical Spirit: Theological Interpretation and Scriptural Imagination for the 21st Century by Amos Yong, and Embracing the Other: The Transformative Spirit of Love (Prophetic Christianity (PC)) by Grace Ji-Sun Kim.