Haunted Heroes, Lousy Leaders, and Deconstructing David

Why “a man after God’s own heart” does not mean what you were told it means.

Yes, it’s been a minute — thanks for your patience since I’m still figuring out my work and writing rhythms in our new place! I will pick up the REstory series (and the mini-series on Hell soon).

The idea for this post has been in the queue for awhile, but there are troubling conversations about King David happening in multiple spaces right now — so this is the week.

Adjusting our assumptions about heroes isn’t easy, and it can feel personal. Part of the inner work of adulthood is adjusting to mismatched expectations concerning the mentors, leaders, caregivers, and institutions from the earlier seasons of our lives. Sometimes the work of processing disappointment, confusion, or betrayal of trust (or even neglect or abuse) requires accompaniment by a therapist or counselor. Sometimes we process alongside friends who support us as we navigate disorientation and try to get our feet back underneath us. Sometimes we attempt to bring accountability into situations where there was none.

This can feel extra complicated in religious spaces (churches and families) because the beliefs or behaviors or loyalties found to be hollow (or hurtful) are connected to communities that gave us our assumptions about ultimate reality. This is a large topic, but in today’s post, I want to describe how Bible reading practices in churches have contributed to hero expectations of the characters in our lives — including King David.1

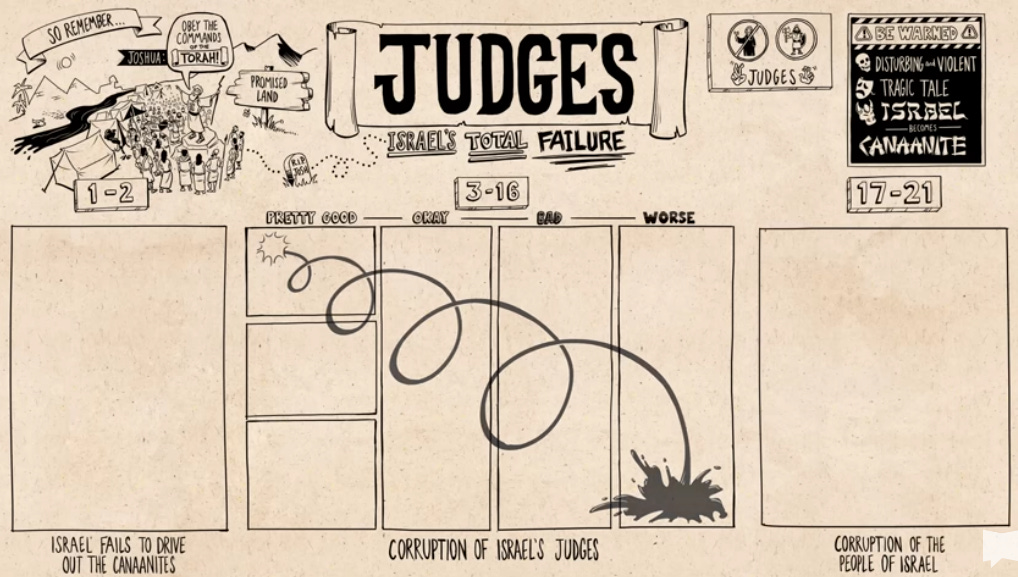

Let me back up before David just a bit. In my community we recently wrapped up a series studying through the book of Judges from the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). We tried to approach it intentionally — with full honesty and also with caution and care for those among us who have experienced violence similar to the stories in the book. Judges is not for the faint of heart — the stories of these regional chieftains (not judges with gavels and wigs) descend on a downward spiral from ok to meh to bad to terrible.

It can be really jarring for folks who’re only familiar with the Sunday School versions of those tales to go back later in life and read the long form of the stories (“Did my second grade Bible teacher really want me to be like Gideon or like Samson??? Yikes.). It can be embarrassing or confusing a couple decades later to realize you were taught a sugar-coated hero version of a horrible story. (It can almost feel like you were being conditioned as a child to accept, admire, or submit to corrupt “leaders.”)2

It’s normal to want to look the other way or skip over failure stories. And yet, I don’t want a Bible without the book of Judges in it, and here’s why: any group that ignores Judges is avoiding the truth that this is what human selfishness and violence and corruption is like. Many churches, families, and institutions are not this honest — to include the worst moments from their community history in the public record and say “We did this.”

Now, the storytelling style of Judges is sparse with minimal commentary3 — the book describes episodes of what the leaders and the people did to each other in an almost matter-of-fact tone — the death toll by the end of 21 chapters shows that Israel kills more of their own people than of their regional adversaries.4

In the storytelling style of Judges, we don’t get the agony and passion that comes with the testimony of the later prophets; instead, surrounding the increasingly devastating stories, we get variations of this repeated refrain: “In those days, there was no king in Israel, and everyone did what was right in their own eyes.”5

But here is where it gets tricky. It would be a mistake to assume that that repeated phrase means we should jump to King David (or to King Jesus) in search of the relief of a “happily ever after” resolution. Those leaps are too big — we need to look more closely at the wider witness in the canon, because there are more downward spirals in the larger context of this testimony.6

Because a little later, in 1 Samuel 8, the people’s demand for a king is emphatically not a good thing — God tells the judge/priest/prophet Samuel, “they’re not rejecting you, they’re rejecting me.” But God tells Samuel to go ahead and give the people what they want, and Saul’s leadership, even though he apparently looks regal, quickly unravels into rebellion, rejection, and rabid insecurity.

It’s then, early in the Saul saga, that we read of his first major offense; the people are on the verge of battle, and Saul panics when Samuel is delayed, so Saul offers the sacrifice, which he was not authorized to do. Eventually Samuel arrives and confronts Saul with the results of his fearful foolishness — the throne will go to someone else: “the LORD has sought out a man after his own heart; and the LORD has appointed him to be ruler over his people, because you have not kept what the LORD commanded you” (1 Samuel 13.14 NRSV).

For many folks in the English-speaking church, that phrase in their Bibles has come with the emotional connotation of warm devotion or prayerful piety — David’s heart is like God’s heart! — and possibly even an wistful implication that we should aspire to be like David in this devotional piety.

But this phrase does not mean what most people have been told it means.

The Hebrew word itself, לבב (levav), commonly translated heart, can refer to the inner person, mind, will, determination, reflection, and memory.7 Beyond the word itself, this phrase was a common idiomatic political expression that shows up in multiple sources in the ancient Near East (ANE). John Walton explains that this was “standard rhetoric” that describes “covenant alignment when a king replaces a rebellious vassal with one who will be more compliant and cooperative;” this is about more about the rejection of Saul and God’s prerogative to replace him.8

Jason DeRouchie agrees, and he shows how the prepositional phrase should be understood adverbially as modifying God’s act of searching (and not adjectivally modifying the noun “man”). He then goes on not only to survey similar prepositional phrases from scripture passages concerning will, intention, and discretion, but he also catalogs seven examples of similar phrases from Babylonian, Hittite, and Sumerian sources across several different time periods.9

In the Yale Anchor Bible commentary, Kyle McCarter translates the phrase “Yahweh will seek out a man of his own choosing,” and he describes how “this has nothing to do with any great fondness of Yahweh’s for David or any special quality of David, to whom it patently refers. Rather it emphasizes the free divine selection of the heir to the throne.”10 The phrase doesn’t mean what I was taught it meant.

Remember that we haven’t even met David yet — even though we will learn a few chapters later that David will be the replacement, the focus of this passage (and the phrase) is why Saul’s failure means he will be replaced by another of God’s choosing.11

There is no doubt that “David” gets a lot of air time throughout the Bible,12 but when we read scripture slowly and in context, we begin to realize that references to “David” do not mean that we should admire or emulate him — at all. Two points should be made here briefly. First, we need to acknowledge the effect of bitter, violent division between northern Israel and southern Judah on history-keeping; northern Israel was decimated by Assyria 150 years earlier than when David’s line in southern Judah was invaded and carried off into Babylonian exile (and then a generation later was able to partially return) — the people of Judah are largely the ones who got to write the history.

Second, many texts throughout scripture reference God’s faithfulness to “David.” Rather than focusing on the individual, if we widen our perspective, we can see how many texts are focusing on God’s ongoing faithfulness to the covenant promises that God made — God will be faithful to the descendants of Judah (David’s tribe) because God is always faithful.13

When we dethrone how we were taught to admire heroes, when we access better tools for understanding ancient idiomatic expressions, and when we reinterpret over-familiar passages within their literary context, we can have more honest, sober conversations about King David.14

Within the canon, reading Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings is like watching multiple car crashes in slow motion, and David is no exception. It feels like terrible reality TV where real people are horribly betraying each other, except that it is the disintegration of a whole nation into violence and selfishness, at their own doing, and often on the backs of the most vulnerable.

Sure, David definitely showed way more early promise than others, but he also wrecks his own life and the lives of many others around him, including his children. He cannot be held up as a hero without deliberately avoiding the tragic trajectory of the testimony in scripture; it is the downward spiral of David’s life that should be the context within which we locate the worst stories, like his assault on Bathsheba (before murdering her husband), who is an innocent lamb in the metaphor Nathan used to confront David.

We should not use the David saga to say “Look, God can use anybody, even imperfect people,” but neither should we look down our noses at David to distance ourselves from his shame. That emotional tendency to jump to either side of the good guy/bad guy binary comes from how we’ve been taught to hear these stories as hero tales.

Instead, we widen the scope of our reading and see God’s agonizing faithfulness to a repeatedly faithless people.

Instead, we ask ourselves “How are we doing this same exact thing — and how can we stop?”

Instead, we ask how we can dismantle church cultures that protect “heroes” and “kings?”15

Instead, we ask who here is like David, and how do I need to be like Nathan?

Instead, we ask how we can build accountability structures into our communities?16

Instead, we ask where other Bathshebas are, how we can care for them, and how we can interrupt predators?17

There is counter-testimony to the mounting tragedies of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings — we find it in Ruth, in the Psalms, in wisdom literature, in Esther, in the prophets, and of course in Jesus.

Remember the warnings about kings from the book of Deuteronomy, portrayed as a speech by Moses to the people as they are about to enter the land:

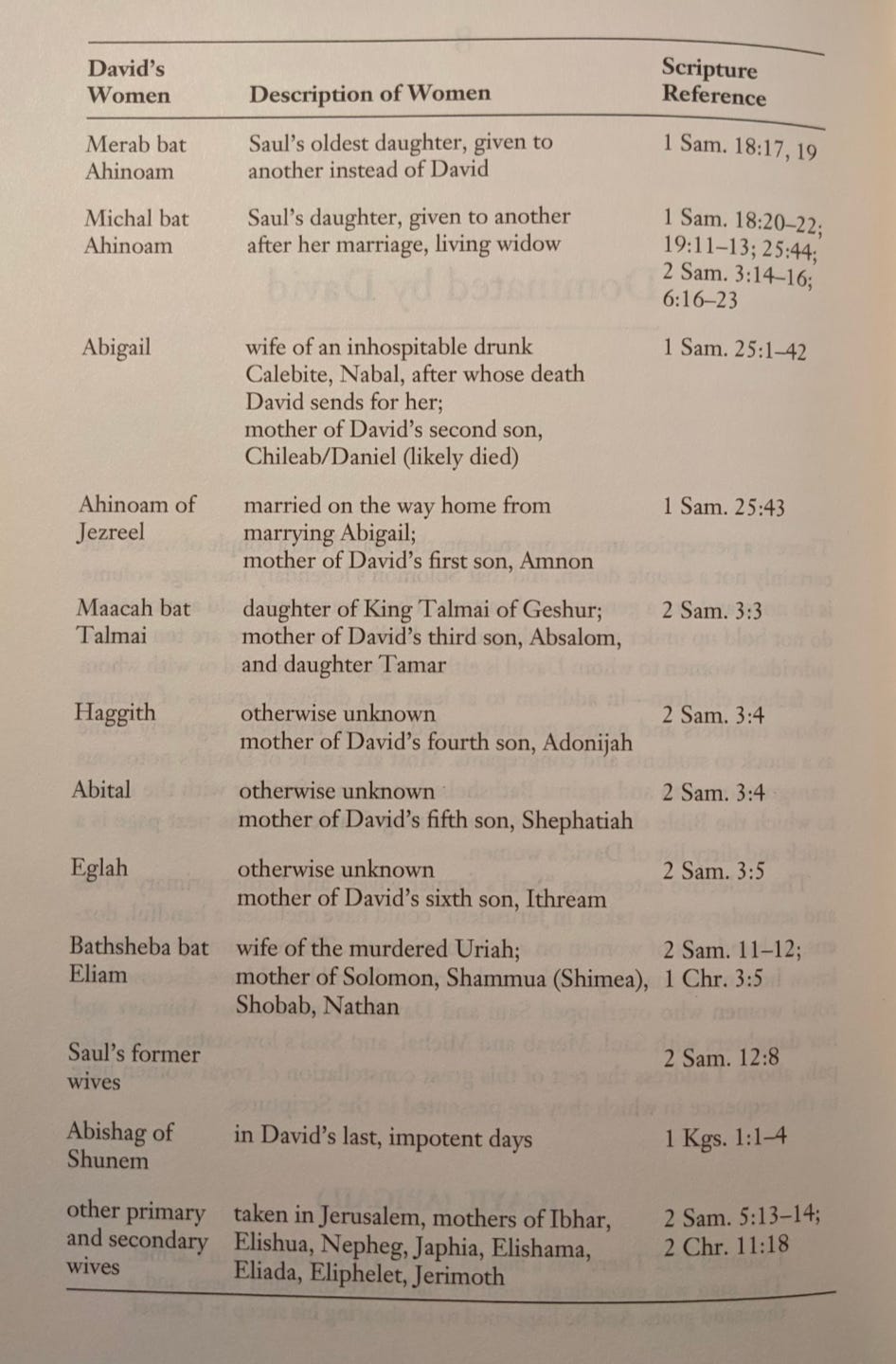

14 “When you have come into the land that the LORD your God is giving you and have taken possession of it and settled in it, and you say, ‘I will set a king over me, like all the nations that are around me,’ 15 you may indeed set over you a king whom the LORD your God will choose. One of your own community you may set as king over you; you are not permitted to put a foreigner over you, who is not of your own community. 16 Even so, he must not acquire many horses for himself or return the people to Egypt in order to acquire more horses, since the LORD has said to you, ‘You must never return that way again.’ 17 And he must not acquire many wives for himself or else his heart will turn away; also silver and gold he must not acquire in great quantity for himself. 18 When he has taken the throne of his kingdom, he shall write for himself a copy of this law on a scroll in the presence of the Levitical priests. 19 It shall remain with him, and he shall read in it all the days of his life, so that he may learn to fear the LORD his God, diligently observing all the words of this law and these statutes, 20 neither exalting himself above other members of the community nor turning aside from the commandment, either to the right or to the left, so that he and his descendants may reign long over his kingdom in Israel. (Deuteronomy 17.14-20)18

David is not a hero — he failed to follow these instructions from Israel’s history as they prepared to enter the land. He started well but ended badly due to his own corruption, and the accountability that comes from bearing witness is there in the scripture if we will read slowly and deliberately.

This matters for our actual lives. Continuing to prop up corrupt characters as heroes is directly connected to anemic accountability that allows predators to stay in power.

The provocative Christian claim is that God is like Jesus (John 5, Philippians 2) — when God showed up in Jesus, from the line of David, God-in-Christ did not act like David.

© 2024 Ladye Rachel Howell. All Rights Reserved.

See Katelyn Beaty’s book Celebrities for Jesus: How Personas, Platforms, and Profits are Hurting the Church.

Krispin and D. L. Mayfield have been documenting their research about the authoritarian and political roots of groups like Focus on the Family; you can find their research here: Strongwilled. This is a lot to process, but this is really important documentation and diagnosis.

Check out the Bible Project’s series of short videos on Biblical Narrative for tools for reading ancient literature in your Bible. Much of the helpful information in these videos is based on Robert Alter’s important work The Art of Biblical Narrative.

I didn’t do the math — see Ellen Davis’ Opening Israel’s Scriptures, p. 154.

See Judges 17.6, 18.1, 19.1, and 21.25.

Remember that almost every book in your Bible was written down, curated, edited much later than the events and experiences they describe, and this is true for Judges — it is obviously a retrospective. So it makes sense why just under the surface, there is a southern pro-David and pro-Judah bias throughout the book if you know to look for:

The prologue to the book (chapter 1) gushes about how great the tribe of Judah is.

Most of the failure stories in the middle of the book involve clans and groups from areas that would eventually be the northern kingdom of Israel.

At the end of the book, the worst atrocities and abandonment are done by the unnamed people of named places - Gibeah in Benjamin and Jabesh-Gilead - which are places that would later be associated with King Saul (who was eventually deposed for his awful leadership and replaced by the young hero David).

All this points towards the possibility that the testimonies that became the book of Judges were likely compiled at a later time — after the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel by Assyria but before the destruction of the southern kingdom of Judah by Babylon almost 200 years later.

This is not the Hallmark channel. ❤️ We should be careful not to assume that ancient languages use body organs as metaphors the exact same way that modern English does. Even the kidneys were considered to be the seat of the conscience (see Psalm 16.7).

https://zondervanacademic.com/blog/hebrew-corner-6

See Jason S. DeRouchie, “The Heart of YHWH and His Chosen One in 1 Samuel 13:14,” in Bulletin for Biblical Research 24:4 (2014), 467-489.

See P. Kyle McCarter, 1 Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes, and Commentary, Yale Anchor Bible (1980), 224-231, especially 229.

Additionally, the phrase “God looks at the heart” in 1 Samuel 16.7 is also primarily critiquing and contrasting Samuel’s noticing of David’s good-looking older brothers. In the New Testament, in Paul’s speech at Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13.16-41), he references this phrase concerning David directly, but even here in this context it is sandwiched between an emphasis is on Saul’s unsuitability and an emphasis on God’s faithfulness to bring Jesus through the line of David.

Out of 150 Psalms, 73 include an attribution to David in the superscription (לדוד); however, the Hebrew letter lamed (ל) has a prepositional range that could render the phrase of David, to David, or for David. This is a longer conversation, but Davidic authorship of those Psalms is not accepted as historical facts by most modern scholars.

For one perspective on this, see “Reading David in Genesis” by Gary Rendsburg.

Another text that is a surprise to many is 2 Samuel 21.15-22. There is a fair chance that David didn’t kill Goliath, but that an older story was borrowed for attribution to the famous king. McCarter points out that “deeds of obscure heroes tend to attach themselves to famous heroes, and there is no doubt that the tradition attributing the slaying of Goliath to Elhanan is older than that which credits the deed to David.” See P. Kyle McCarter, 2 Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes, and Commentary, Yale Anchor Bible (1984), 447-451, especially 450.

Please watch Sara Barton’s 2019 Pepperdine Lectures keynote address on Bathsheba, and then go read Walter Brueggemann’s book The Prophetic Imagination — it should be required reading for every minister and elder.

It shouldn’t take investigative journalism to uncover the lack of accountability in systems that keep predators in power. This is everywhere — the large scale documentation reporting predatory behavior, sexual abuse, and cover-ups in Roman Catholic, Southern Baptist, and Anglican churches is already easily accessible. Any other church or denomination is foolish to assume it’s not happening under their own roofs.

Many scholars attribute Deuteronomy (and much of the “Deuteronomic History” that includes all the David stories) to the reign and influence King Josiah, which would of course limit the accessibility of that written material to a time several generations after David. For our purposes today, the point is the critique is there within the canonical witness.

This is great! Thank you for touching on this subject as I've seen the memes and posts equating David and Trump!