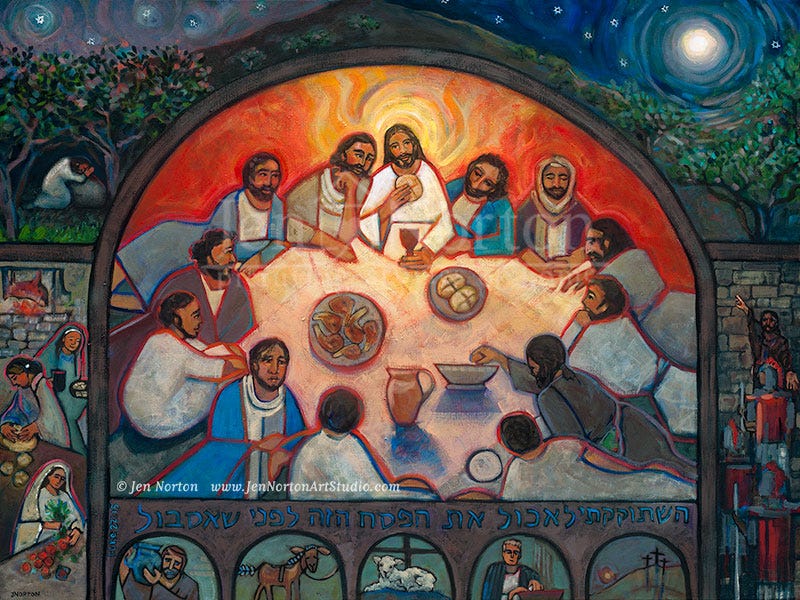

Today is Maundy Thursday, the day on the church calendar marked to celebrate Jesus’ final Passover meal with his disciples (mentioned in all four gospels) and also how he washed their feet (only in the gospel of John).

Many churches are walking together through the season of Lent right now. These forty days of reflection and repentance guide us to refocus on where we need to make more room in our lives for Jesus and his love for the world. Through Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Easter Sunday, we reflect on the death and disintegration that are everywhere in the world, and in our grief we hold onto the hope that God–in–Christ has defeated death, and that the Spirit is already sparking new life within the decay.

In this past year, I have written several posts describing healthier ways to talk about the meaning of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. When we realize the problems with medieval atonement theories, we find there are multiple, larger ways to return to scripture to understand anew how “salvation” comes from the gift of Jesus to the world.

For a few centuries now, many of us have been taught to assume that the main goal of the cross is salvation of individual souls—and if “salvation” was the answer, then the question behind that was often “Why did Jesus have to die?” (and sometimes inside that question is usually another question about “how atonement works.”)

But we need to study the cross and resurrection in the context of ALL of Jesus. When we widen our view to all of Jesus (incarnation, life and teaching, crucifixion, resurrection, ascension, Pentecost, second coming), we start to realize that the salvation of individual souls might be too small. That’s not big enough to be the ultimate question or the title of the story—God’s dreams are bigger than that.

All our learning about Jesus happens within the context of a great cloud of witnesses—all around the world, in hundreds of languages, people have been discussing the meaning(s) of the cross for nearly 2000 years—there has never been only one. As we read and interpret scripture about the death and resurrection of Jesus, we are joining a beautiful, centuries–long conversation.

Jesus' disciples didn’t understand even when he spelled it out for them ahead of time. In Mark 8.31-35 and Mark 9.30-37 and Mark 10.32-45 he tells them three times that he’s going to Jerusalem and will be murdered by violent humans and raised back to life. Here at the hinge of this short, intense gospel, Jesus repeatedly explains the suffering that is about to happen to him, and in each explanation he is also redefining power. And they’re still struggling to understand a few chapters later when he re-frames the Passover meal for them in Mark 14.

I have often heard this passage read during a communion reflection, and when that happens, the speaker usually reads Mark 14.22-25 (which in many versions has the subtitle “The Institution of the Lord’s Supper” inserted over it by the translators). But I think there is a much wider angle to view what’s going on here. More on that in a bit.

I’ve shared before about how our understanding of the “gospel” expanded when we moved to another country . As we were immersed in language and culture learning, we came to realize that the way we had been taught to think about the cross wouldn’t translate into the context there. We had to put on our research hats, because it turns out we had mostly been taught one atonement theory as the (only) definition of the gospel. We were amazed to learn how many options there were for approaching the cross from the witness of the church over time.

One of the many resources we encountered in that research season was the book Preaching a Better Atonement by Jason Micheli, who is a minister in the DC area. He tells a story about one night when he was at a Buffalo Wild Wings for a trivia night with his son, competing against a few other teams at other tables when the question came up, “On which Jewish holy day was Jesus crucified?”1

They could overhear the guys at the table next to them, and one of them turned to his teammate and said, “Hey you're Jewish, what’s the answer?” And his buddy answered, “Yeah, I’m Jewish—I don’t know anything about Jesus.” But apparently Micheli’s son had already outed his dad as a minister, so they asked him, “Do you know the answer?” And since they were already ahead in their points, Micheli told them, “Passover. Jesus’ death happens on Passover.”

And the Jewish guy on the team next to them said, “Wait what? It’s Passover? It’s not Yom Kippur? If Jesus dies for our sins like you Christians say, why does he die on Passover and not Yom Kippur? The way you Christians talk about Jesus’ death always makes it sound like it’s a sacrifice on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement).” Micheli was startled by the realization that this might actually be the most important question.

For a very short summary, within Israel’s festivals and Holy Days, Yom Kippur is the Day of Atonement, now considered the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. You can read about it in Leviticus 16 (and you can also read my research about it); it was the one day a year when the tabernacle was cleansed from sin and impurity. A priest entered the Most Holy Place to sprinkle it with blood (since ancient peoples thought of blood as the source of life and kind of like a detergent for impurities). Also on that day, the priest confessed the sins of the people over a goat that was then led away into the wilderness alive to symbolically carry the people’s yearly sins far away from the sanctuary.

But Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection happen on Passover weekend, which celebrates how God delivered the people from slavery and oppression under Pharaoh in Egypt—you can read about the Passover in Exodus 12-14. In the gospels we see Jesus moving toward Jerusalem, seeming to navigate time and days so that his death and resurrection would be a Passover event. It is significant that Jesus casts his death and resurrection as a Passover—as an exodus.

Passover isn’t about forgiveness but freedom. But many of us may have heard that the goal of the cross was to trigger God’s forgiveness.

As if God couldn’t or wouldn’t forgive without a blood sacrifice? As if God couldn't or wouldn't forgive us if Jesus didn't die as our substitute? As if God wasn't already revealed long before Jesus as the source of all forgiveness?

Forgiveness is not enough, we need liberation. Micheli reminds us that “sin isn’t just something we commit… sin is also something that’s done to us—by others. Sin isn’t just something that we’re guilty of, it’s also something that binds us. It isn’t just something we need to be forgiven of as much as it’s something we need to be liberated from.” We need deliverance from oppression and protection from death.

The Day of Atonement is still really important in Israel’s history—Yom Kippur is a yearly cleansing of the sanctuary and removal of sin and impurities from the community. But to reframe Jesus’ death and resurrection as a Passover story means Jesus wants to accomplish our deliverance from captivity—to death and sin and the satan.

But I think we need to widen this frame even more—it’s not just a shift from Yom Kippur to Passover, but a shift from Leviticus to Exodus.

Ellen Davis is an Old Testament professor at Duke, and she writes that when she went to see the 1998 movie Prince of Egypt, when God has the showdown with Pharaoh, and Moses finally leads the people through the parted Red Sea, she thought the movie was half over and was startled when the credits began rolling and the lights came back on. Because liberation from the oppression of Pharaoh and his empire of death is only half of the Exodus story.3

The goal of the Exodus rescue is for the people to get to Mount Sinai and meet with God—to enter into covenant with God their liberator. The point of the dramatic deliverance is that God wants to live among them, to tabernacle among them.

They need to meet God at Sinai to learn how to host the presence of this God so they can show the whole world what this God is really like—that is the work of a “kingdom of priests.” Exodus 19 reveals that the point of rescue was to extend revelation.

But it’s a rough road leaving Egypt for Sinai—liberation is hard work. They get thirsty. They get hungry. They struggle to trust God along the way. They grumble. They start to fantasize about how good slavery was. They complain. God feeds them and goes with them anyway.

Then when they arrive at Sinai, God declares his delivering love to them, and the people say yes to God’s covenant proposal, and there’s a covenant ceremony. But then while Moses is up on the mountain receiving the instructions for building the tabernacle, they break the covenant promises they have just made, and they make a golden calf to worship.

This is like committing adultery on your wedding night—God is angry and broken-hearted. Moses has to intercede to convince God to stay present and go with them.

And God listens to Moses and does what he asks—God won’t abandon the people. And this is where we get the beautiful passage in Exodus 34 where God’s goodness and glory pass in front of Moses and God announces God’s full identity—compassion and mercy and kindness and faithfulness and forgiveness are spilling over each other.

It doesn’t mean that human destruction won’t have consequences—it still does, but God’s compassionate faithfulness always outweighs it. And they proceed with building the tabernacle.

If we look closer at the mountain scene in Exodus 19-24, we realize that God is initiating the new covenant ceremony with this people right in between their grumbling and their betrayal. What kind of God does that? At this ceremony, Moses sprinkles the people with blood to consecrate them and inaugurate the covenant the people are entering into, and some of them are allowed to go further up the mountain with Moses and share a covenant meal with God.

But when we get to the heartbreaking betrayal of golden calf worship, this is also sandwiched between two matching sets of chapters. In Exodus 25-31 we get nobody’s favorite seven chapters—the instructions for building the tabernacle. And then in Exodus 35-40 we get what almost looks like a word-for-word repeat of tabernacle instruction chapters, and in between is the golden calf episode.

In the first section you’ll find a verse: “You shall make a table of acacia wood two cubits long,” and then in the second section you’ll find a matching verse: “And he made the table of acacia wood two cubits long.” On either side of the golden calf you have matching sets of chapters. Before the golden calf story are the instructions for building the tabernacle. And after the golden calf story they’re actually following the instructions for building the tabernacle.

And it might sound a little boring. The repetition might feel tedious to us, and it’s not a storytelling style that we’re used to. But we need to remember that all the tabernacle construction information is about hosting the presence of God. All those repeated details make the audience slow down, and it slowly dawns on us—

—after such a terrible rejection, God is going through with this. They’re building the tabernacle, and God is really going to remain in covenant with these people, even after what they’ve just done.

Which brings us back to Mark 14. With Exodus in our imagination, we can read this passage with a wider lens and realize that when Jesus talks about the “blood of the covenant,” this is Sinai language. This consecrated relationship was inaugurated in between the grumbling that came before and the betrayal that followed.

If you can, take a few minutes and read Mark 14.10-31. When we read the wider passage, being sure to include the section before and after what’s normally read in v.22-25, we realize that this covenant meal comes sandwiched in between betrayal and denial.

Jesus’ offer of bread at this sacred Passover meal—saying this is my body—and then giving them the cup—saying this is my blood of the covenant—this is Exodus language. And this intimate, sacred covenant meal comes between betrayal and denial—between traitors and deserters. Jesus knows that Judas and Peter and the rest will fail and he still offers them a covenant meal, because Jesus remembers the faithlessness of the people before and after the covenant was inaugurated at Sinai.

Exodus is about more than rescue; the larger goal of deliverance is to enter into covenant with God—when the people of God learn to host the presence of the Holy One, they can become a kingdom of priests who can offer the presence of God to the world.

Communion at Passover also points to a wider vision—the larger goal of salvation is to become a people who mediate God’s love to the world.

God’s dreams are bigger than salvation for individuals. God knows our trust is timid, our affection is anemic, and our faithfulness is feeble, and God still eats with us and enters into covenant with us and wants to tabernacle with us so we can, like our ancient siblings, become a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.

Death and destruction are filling the news headlines every day. Too many Christians are increasing the suffering in the world right now, if not directly then indirectly by voting for increasing others’ suffering or cheering it on.

But it is Jesus who shows us what God is like. Jesus’ suffering to enter into covenant with humans reminds us of God’s suffering to enter into covenant with humans. When will churches look like this Jesus?

©2025 by Ladye Rachel Howell

See Jason Micheli, Preaching a Better Atonement.

Of course, it is the book of Hebrews that uniquely explores sacrificial metaphors for Jesus to the fullest extent, and I am not denying that. But even Hebrews may hold a wider vision than many of us heard in church—I would encourage you to read David Moffitt’s book Rethinking the Atonement: New Perspectives on Jesus's Death, Resurrection, and Ascension or listen to this podcast interview. You could also read Christian Eberhart’s book The Sacrifice of Jesus: Understanding Atonement Biblically or listen to this podcast interview.

See Ellen F. Davis, Opening Israel’s Scriptures, chapter 2.