The film Princess Bride came out when I was in fourth grade, and I’ve seen it more times than I can count. One of the (many) memorable scenes from the movie that sticks in people’s minds is the kidnapper-for-hire Vizzini’s repeated exclamation, “Inconceivable!” Vizzini is so confident in his own smarts and in the secrecy of his thorough, flawless plan, that when it appears a masked man is expertly following them, he blurts out “Inconceivable!” over and over again as the man in black gains on them at every turn. He can’t conceive of what he was so sure was inconceivable, but there were more factors in play than he was aware of.

Eventually the hired hand Inigo (who by the end of the film turns out to be the wiser one) turns to Vizzini and says, “You keep using that word — I do not think it means what you think it means.” This now classic line pops up in our memories whenever a word’s overuse or misuse shows up in our lives in a funny or ironic way, and I couldn’t get Inigo’s line out of my head as I was preparing this REstory series on hell. All language changes over time, and often our translated religious vocabulary needs to be reexamined — is that really what we mean? Is that really how that word or phrase was used back then? Is that really what God is like?

When it comes to hell, we need permission to stop and ask each other, “you keep on using that word — I do not think it means what you think it means.” Because it turns out hell is not in your Bible. Sheol, tartaros, hades, and gehenna are in your Bible. But not “hell.” More on that in a minute.

Side note 1: The Rapture isn’t in your Bible either — that doctrine was invented in the 1800’s and I won’t have the space to cover it here in this series.1

I am writing with so much care this week, because of how many people who have shared their grief, anguish, and frustration about how the fear of hell has affected them and caused trauma.2 In the next few posts I am going to outline the direction for healthier conversations about the church’s history with “hell” — I think you might find some relief, and though this won’t be exhaustive, I will link resources for further exploration and study.

But where should we start?

In my experience, starting conversations on “hell” by examining Bible verses isolated from their context is unwise and usually results in frustration. This is largely because it misses the fact that the people in the dialogue usually already have different pictures of God serving as their lenses for life and scripture. Make no mistake — when anyone is researching “hell,” they are investigating competing portraits of God — and those different views of God will largely determine the lenses they’ll use to read scripture.

We’ve said before that salvation defined as individuals going to heaven in order to avoid hell was never the ultimate goal. Sometimes, learning that “hell” wasn’t meant to be a primary motivation for faith comes after the paradigm shift first towards the God of New Creation, which transforms and enlarges our motivations. Notably, when we center the narrative on the God of New Creation, this fundamentally changes our lenses for reading scripture.

So of course examining “hell” is connected to the prolonged conversation we’ve already been hosting here; the contrast between “Story A” and “Story B” is an important foundation (go back to the REstory 1 post if you need a refresher). Story A is motivated by avoiding negative consequences from a punishing God who has to be convinced by Jesus’ payment to reconcile with humans. But Story B offers a larger story about a God who is continually pursuing humans and inviting us to participate in New Creation.

Side Note 2: Some folks who have been deconstructing “hell” have been told that by rethinking eternal punishment, they’re being “soft on sin.” But Story B that centers on the resurrection actually takes all the selfishness, violence, and greed in the world more seriously than Story A (that is mostly concerned with avoiding consequences). Story B has much deeper resources for healing the destruction that humans cause in the world.

We need to keep examining the center and the size of the narratives we’ve been told about God. Many churches have hell-avoidance at the center of their “gospel.” Anytime the basic motivation for salvation is fear of going to hell, then “hell” is at the center of their good news.3 This can be true even in churches that don’t use the word hell very much.

For example, I’ve heard the “gospel” summarized by a church elder as a parachute when the plane is going down: you’re going to need this in order not to die/ crash/ burn. He doesn’t have to say the word “hell” for it to be the center of his message; this is fear-based motivation even if it is told in a cheerful tone. Another time, a professor in a seminary classroom was deconstructing “hell,” and a classmate (a career missionary) responded, startled, “Wait, then what are we doing???”4

If you take away “hell” and there’s not much story left, then “hell” is at the center of the story.

“Hell” at the center of the story creates a small, uninteresting, fear-based narrative about avoiding punishment — instead of an expanding narrative of participation in New Creation that leads us to risk it all with acts of love. REconstructing the larger Resurrection-centered story is part of putting “hell” in its place.

So this helps us examine the size of “hell” — because within scripture, you could say “hell” is a footnote, not a feature. In addition to a “footnote,” I can also appreciate the analogy of an alarm clock for reducing the size of “hell” (an analogy used by some teachers I know). Imagery alluding to extreme or final punishment occurs with rare frequency in scripture, usually to get the attention of someone who needs to be jolted awake. But if you need an alarm clock all day long to stay awake and love God and flourish in your life, something is wrong.

We already know that it is possible for someone to focus on an item in their peripheral vision and miss what’s right in front of them. It is possible to focus on one detail so much that we force it into the center and end up distorting the whole story. For example, cyclists and other racers are aware of the phenomenon of “target fixation” that occurs when the rider or driver focuses on an obstacle so much that they end up colliding with it. Have we been taught to fixate on the wrong center, so that our out-of-focus lenses blur the bigger story and lead us away from it? When it comes to “hell,” what if certain verses not only became twisted into the center but also over-literalized?

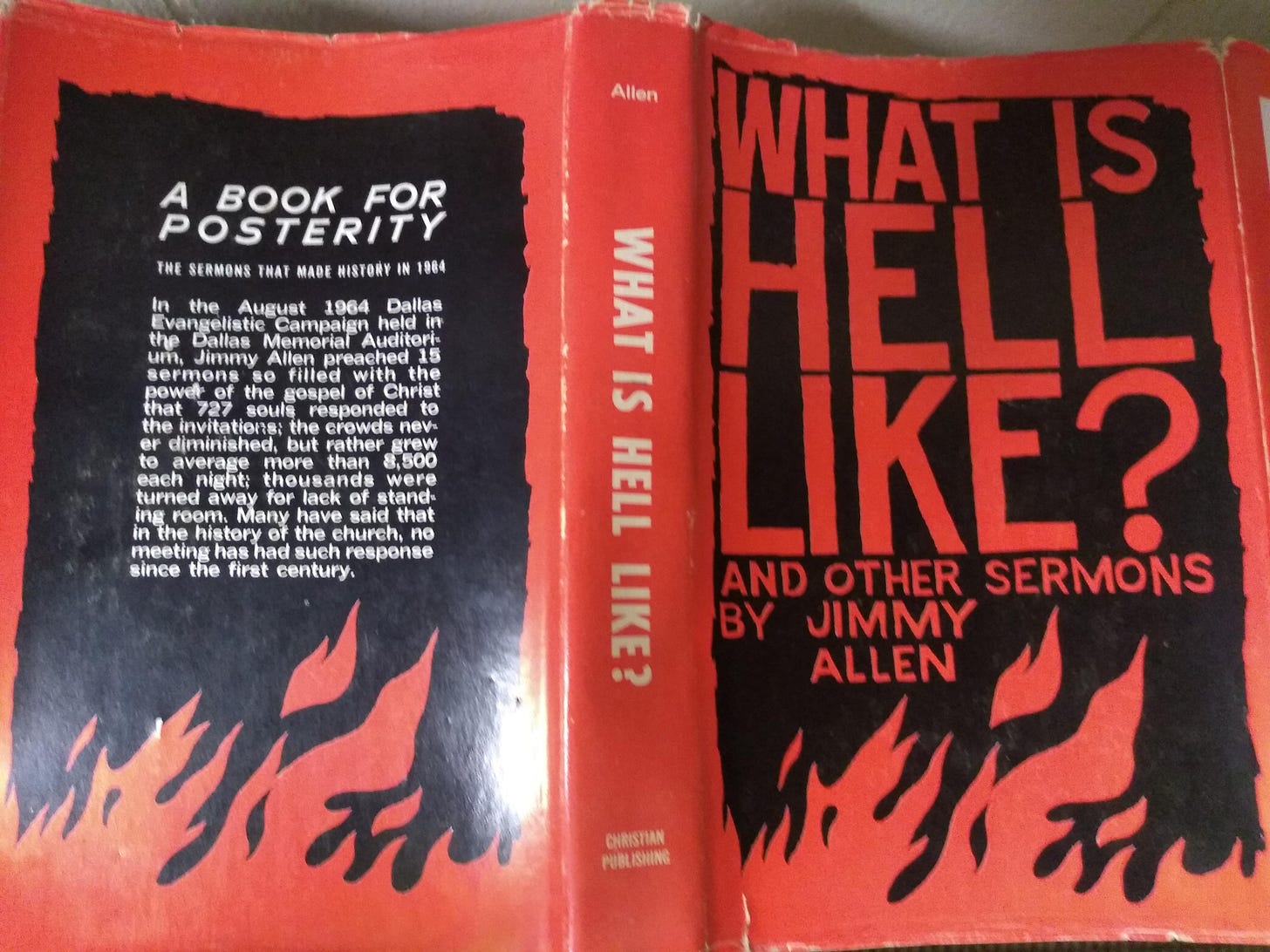

We inherited ideas about “hell” from others (who received it from others, who told them, etc); none of us currently wrestling our way through this complex conversation are responsible for inventing it. It goes back several centuries in fact — the current images and concepts associated with the English word “hell” have been more influenced by Dante’s Inferno, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and Jonathan Edwards’ sermons than by scripture. There is more influence on western assumptions about “hell” from inherited late medieval imagery than there is from first century scripture and audiences.5

Before I close today, we need to briefly mention that centering a late medieval view of “hell” also distorts how people in positions of power persuade others. Making hell-avoidance primary leaves the door open for churches and ministers to influence people with fear. Even here multiple motivations are possible; obviously, a minister or elder could truly believe in a hell-centered story and be sincerely moved by benevolent fear on behalf of others. But how can church members tell when those in power may also be coasting on the fear of “hell” (or weaponizing it?) in order to maintain attendance, donations, or the leaders’ egos? These are really important questions.

Similar to when we surveyed ten options for atonement theories, in the next post, we will begin to look at the words and verses in their ancient contexts and also begin to describe the multiple views that scholars and theologians hold on how to interpret “hell.” I hope it feels like we have permission to start saying to each other, “you keep using that word — I do not think it means what you think it means.”

Back in my very first post at Go Out In Joy, I quoted a line from a children’s book: “If you ever find yourself in the wrong story, leave.” When we walk away from the god of Story A, we are walking away from a story that uses guilt, shame, or fear as primary motivations for pressure and persuasion. When we walk toward the Story B God, we’re walking into a story of Original Love that promises to creatively heal all the wounds in the universe.

It’s almost inconceivable :)

© 2024 Ladye Rachel Howell. All rights reserved.

You could say that a discussion of The Rapture will get “Left Behind” (wink). If you’re looking for resources to understand or unlearn “Rapture” doctrines, consider the following resources: Michael Gorman’s book Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness - Following the Lamb into the New Creation. You may also appreciate Nadia Bolz Weber’s “welcome” reminder of the meaning of the word “apocalypse.” Additionally, Richard Beck gratefully describes the value of an “amillennial” church that formed him. D. L. Mayfield also describes how the weight of end-times anxiety in evangelicalism formed her heart, mind, and body and how she’s still healing from that harmful formation.

Check out Dan Koch’s Spiritual Harm and Abuse Screener and accompanying handout. trauma assessment? You will also find Elaine Heath and Charles Kiser’s book Trauma-Informed Evangelism: Cultivating Communities of Wounded Healers helpful.

Try asking consecutive “why” questions about core faith propositions: “why do you believe/practice ______?” Then follow up that answer with the next “why,” then ask “why” again (etc.); sometimes this examination leads to the realization that hell-avoidance is hiding underneath everything.

It is true that inheriting a faith that has hell avoidance at the center means that many ministers and missionaries and members may have hell avoidance at the center of their identity. It is also true that demonstrating how a hell-centered faith is an inherited misinterpretation could threaten a core identity element for some people. This is an opportunity for deep compassion since it takes unbelievable strength to admit you’ve been wrong about something for a long time. This is also an opportunity for deep courage for many to trust God through such a conversion of their understanding of God.

I’m not using medieval as a derogatory term, but to locate ideas within their historical context. In the coming posts, we will also go back before the medieval period in order to trace the history of the development of doctrines of final judgment. If you need some fresh imagery to dislodge ingrained pictures of forever fire, I’d highly recommend reading C. S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce or Tolkien’s Leaf by Niggle to dethrone the medieval imagination we’ve inherited.