REstory 16: Hell is "Literally" a Hot Topic

How about we widen our humility about "hell" vocabulary?

I have to confess that as a parent I really, really didn’t like Amelia Bedelia books — the repetition of her eight-syllable name over and over again and her hyper literalism somehow made my brain itch, and I would bargain with my kids to read-aloud anything else.

However, as a child I loved reading the quirky stories of a hired housekeeper who understood all the instructions so literally that she did everything wrong (and somehow everything was fixed by baking yummy treats). It’s a great way to teach young readers how to interpret a language full of idioms (sewing tiny clothes in order to “dress the chicken,” sketching on paper when she was told to “draw the drapes,” and hosing down a woman on the porch because it was a wedding “shower”).

Of course starting this post on hell with Amelia Bedelia has nothing to do with my annoyance at those books… (side eye emoji here) and everything to do with our expectations about language: meaning, allusions, metaphor, imagery, idioms, analogy, hyperbole, metonymy, rhetoric, and more. Maybe we expect it already in poetry and parables, but there are many common ways that language carries meaning without exact precision:

Their marriage is on the rocks.

She blew up at him.

He cracked under pressure.

They’re staying home to recharge their batteries.

She’s solid gold.

They swore loyalty to the crown.

He’s in an uphill battle.

They’ve crossed the Rubicon.

The point is that we use non literal imagery in our language to communicate everyday, and ancient cultures did as well. Languages also vary regionally and change over time. For example, for most of my life, the phrase “out of pocket” has meant having to pay your own expenses, or it could mean being unavailable or unreachable. But my now young adult kids tell me there’s a newer meaning; “out of pocket” (or “outta pocket”) can describe when someone is unexpectedly cruel or surprisingly offensive. Who knew? (Actually my kids knew :)

We need permission to widen some of our expectations for the words and phrases we encounter in the ancient texts in our Bibles — I hope it is a joyful permission. I wrote last week that whenever anyone researches “hell,” they are investigating different portraits of God, and that is really important. Whatever we think God is like becomes our lenses for interpreting everything else, including language about final judgment — so let’s take a look.

Remember back in REstory 5 when we surveyed ten atonement categories, but acknowledged that most people only hear one or two from preachers or teachers at church? Well, when it comes to “hell,” there are five main categories under consideration, and proponents of all of these categories claim scriptural support, and church members deserve the chance to examine and consider each one.

Each of these has multiple names as well as variations, subcategories, and potential overlap with the other views depending on the scholar; today’s post will only summarize these positions, and we will continue the discussion in the next post.1

Eternal Conscious Torment - some people will continuously burn in hell forever

Annihilationism - some people will burn up and cease to exist

Purgatory - there is a place/ time for required purification exists after death but before eternal life

Metaphorical - the intense imagery describing final punishment was not meant to be literal in its original context/audience

Ultimate Reconciliation - after resurrection and judgment, God will make all things right

Eternal Conscious Torment ECT (also known as “Traditional” view, the “Literal” view or “Infernalism”) claims that after death, the wicked or those who have rejected God will be condemned to experience unending fiery torture for all eternity. This is also called the literal view because it relies on surface descriptions and leaves little room for poetic imagery.2

Annihilationism This view (also known as “Conditional Immortality” or “Terminal Punishment”) claims that those who reject God will suffer punishment, but that punishment will involve “destruction” in that their death will be final — the wicked will cease to exist while those who love God will live on in a resurrected immortality.3

Purgatory claims that there is a possibility after death for people to receive healing and purification required to enter salvation with God. This is historically the Roman Catholic view.4

Metaphorical Language This view emphasizes the nature of symbolic language and how strong, vivid vocabulary was used both to urgently warn hearers to motivate them towards action and also to comfort those suffering under oppressive empires, but without the necessary assumption that they were literal descriptions of actual places.5

Ultimate Reconciliation (also known as Christian Universalism) claims that in the end, after resurrection and judgment, everyone will be reconciled to God. Many from the Eastern branches of the church find themselves in this category.6

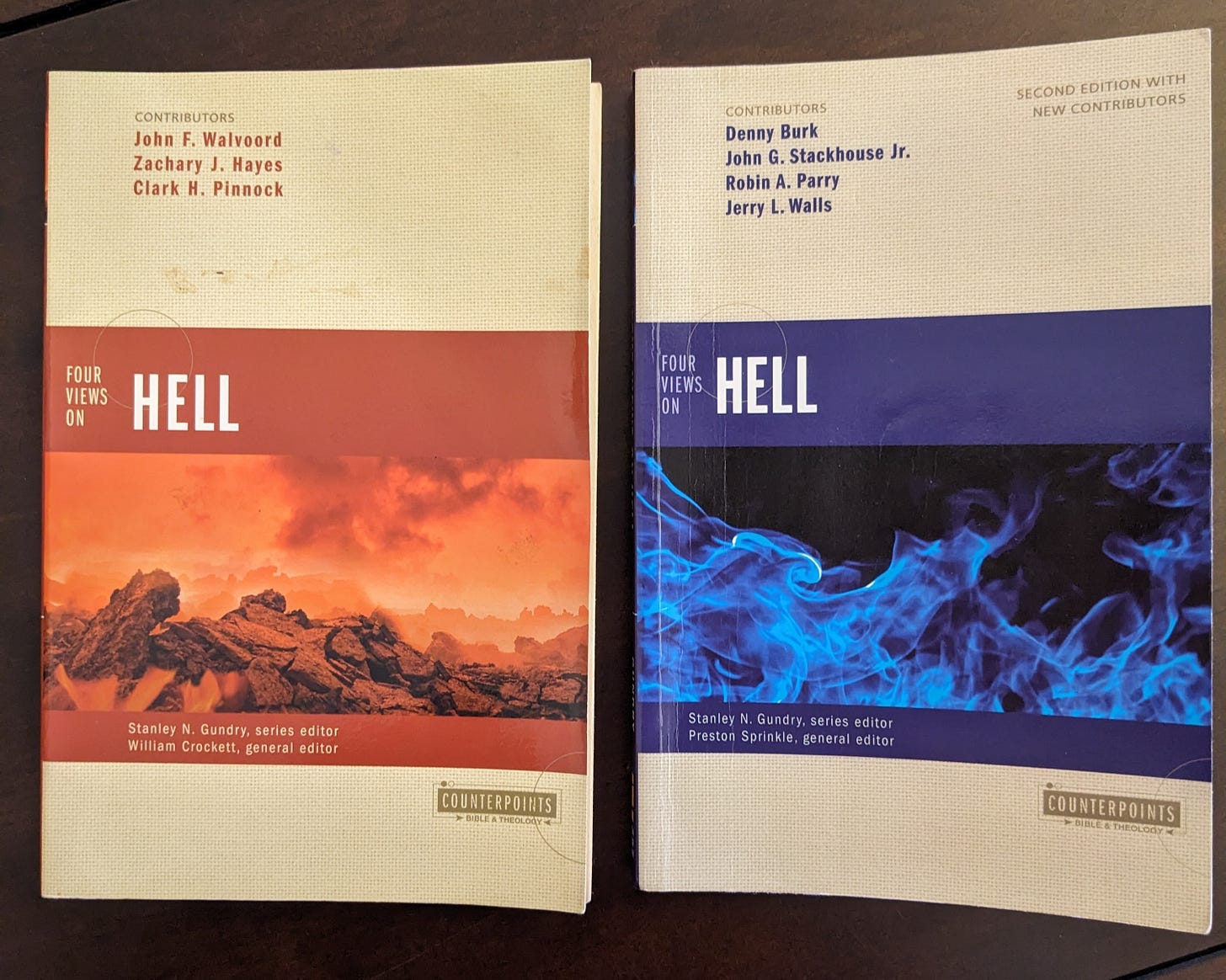

These two books were published in 1996 (left) and 2016 (right), and they don’t contrast the same categories. In the two decades between, the conversation has shifted. The 1996 version included the first four categories above; the 2016 version drops The Metaphorical View and includes instead Ultimate Reconciliation /Christian Universalism.

So what are we talking about? I wrote in the last post that “hell” is not in your Bible, but that sheol, hades, tartaros, and gehenna are. I also shared that there is more influence of western assumptions about the English word “hell” from late medieval and renaissance imagery than from scripture. This can vary among translations, but for anyone struggling to detach their view of God from imagery inherited from Dante, Milton, and Edwards, it could be very helpful to cross out the English word “hell” in your Bible and write the Hebrew or Greek term used in that verse next to it:

Sheol. Used 66 times throughout the Hebrew Bible, sheol is the term used for the realm of the dead for both the righteous and the unrighteous; it can also represent death as a destination or “the grave.” Interestingly, in Psalm 139.8 the psalmist provocatively claims that they would find God there in Sheol.7

Hades. This term means the nether-world or the realm of the dead. It is found only 10 times in the New Testament: Matthew 11.23, 16.18; Luke 10.18, 16.23; Acts 2.27, 2.31, Revelation 1.18, 6.8, 20.13, 20.14.8

Tartaros. This term also signifies the nether-world, but sometimes “lower” beneath Hades in Greek thought. It is only used once in 2 Peter 2.4.9

Gehenna. This Greek term is transliterated from the Hebrew name “valley of Hinnom” and refers to a valley on the southwest side of Jerusalem for associated imagery of judgment and punishment — more on that in a minute. It is found only 12 times in the New Testament: Matthew 5.22, 5.29-30, 10.28, 18.9, 23.25, 23.33; Mark 9.43, 9.45, 9.47; Luke 12.5, James 3.6.10

There is no question that these words are negative, and that they are often used with urgency or for persuasion. Gehenna is the stronger term and the one most used by Jesus in the gospels — it is generally agreed that hades and tartaros are closer equivalents to the “realm of the dead” idea of sheol (in fact, gehenna is never used to translate sheol into the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures).11

I point out word counts and their ranges of meaning not to make a final theological claim but rather to open the beginning of a longer conversation. These terms need to be interpreted in their canonical, historical, literary, rhetorical, and ancient cultural contexts (and freed from medieval baggage).12 And of course, there are passages in scripture that are relevant to this conversation that don’t use tartaros, hades, or gehenna; we have to investigate passages that hint at judgment, death, and punishment or use imagery of fire, outer darkness, and gnashing teeth — even if they don’t use the words above.

When reading texts from the first century, we should not automatically assume that they mean what our English words mean. Instead, we should assume first century communicators would be using words and phrases based on how they thought their audience would hear them — speakers and writers have ideas about what meanings are already in the imaginations of their audience.13

That means we need to study what gehenna might have meant to a first century audience. Because all language — our words and phrases and how we’ve learned to use them — is contextual, social, and dynamic, often with regional variations and affected by events in history.

In Hebrew, Ge Hinnom means Valley of Hinnom, and it is a valley on the south/southwest side of Jerusalem mentioned in Joshua 15.8, Joshua 18.16, Nehemiah 11.30 as a geographical marker. While it’s difficult to determine precise boundaries from 2500 year old descriptions, you can visit Gehinom today.

Both King Ahaz ( 8th century BCE) and his grandson King Manasseh (7th century BCE) angered God by using the Valley of Hinnom for idol worship and —despicably— child sacrifice by fire (mentioned in 2 Chronicles 28.3 and 33.6). However, we read in 2 Kings 23.10 that his grandson Josiah “defiled” that space so as to put an end to the violent idolatry in that space.

Then in Jeremiah 7.27-34, the prophet brings a message from Yhwh, referencing the evil practice of child sacrifice in that valley “which I did not command, nor did it come into my mind.” The prophecy goes on to describe how dead bodies will pile up in that valley when joy has ended because Jerusalem and Judah have been destroyed (this passage is echoed in Jeremiah 19 and Jeremiah 32).

This is where we should begin our investigation of gehenna. Instead of Dante’s medieval imagination, we should start with the first century audience’s communal memory of the shameful acts of horror that their own ancestors committed, precipitating events that led to Babylonian invasion, exile, and destruction. This would still be provocative warning language almost 500 years later during the time of Jesus.

Side Note: There is a really common misconception that by the first century the valley of Hinnom had become one of the city garbage dumps of Jerusalem where trash (or even dead bodies?) were burned and continually smoldering. There is no primary source evidence that this is true — the idea may have begun with a 13th-century rabbi; however, this false claim continues to be circulated without fact-checking.

Our English word “hell” has so much medieval baggage that I don’t think we should use it. Through no fault of our own, many of us have inherited arrogance about our English translations. In order to make the familiar strange, it can bring a fresh dose of humility to instead read or say “Gehenna” every time it’s in the text.

Before I wrap up this post, I want to point out that another important word or concept to consider is the Greek term aionios, the adjective that is translated eternal, everlasting, forever, ageless, of the ages. A crucial question in these reconstruction conversations is how this word was used — how long is forever? Or what is forever like? Scholars disagree whether this word describes something quantitative (either prolonged or unending duration) or qualitative (characteristic of God’s transcendent, ageless realm) or both?

However, this is another place where we need to widen the frame and ask ourselves again if the story we think we are in is affecting the scope of our question. Are we in an avoiding hell story or a New Creation story? Because the adjective aionios is used 71 times in the New Testament — 7 times it modifies nouns like fire, judgment, punishment, sin, and the remaining 64 uses of aionios modify nouns like life, redemption, salvation, comfort, or glory.14

The goal of this post has been to set the table for the next conversation (truly — we are just laying out the bowls and spoons and cups today). I have described the words, phrases, passages, and assumptions that come together into the four categories above so that no one has to stay stuck but can find resources for learning beyond what they inherited.

We will continue this conversation in the next post, but for now, let’s not make the mistake of Amelia Bedelia — whose over-literalized interpretations led to foolish or obnoxious behavior — and hope that by baking sweets everything will be fine.

We have permission to Go Out In Joy. We can step outside of the limits of proof-texting used to support medieval imagery, and when we do, the first question should be what kind of story are we in? Some of us may have been given the idea that we are in a “heaven or hell” story, but if we search scripture for the phrase combining the terms “heaven and hell,” you won’t find it there.

Instead what you will find —over 150 times— in scripture is talk of “heaven and earth” paired together as the realm in God’s care. This is where we find ourselves: invited to join this coming kingdom where we bring God’s healing love from heaven to earth.

© 2024 Ladye Rachel Howell. All rights reserved.

This whole conversation is adjacent to but not the same thing as discussion about identity boundaries of “salvation,” which is a key pillar and motivation of evangelical theology. This begins with a concern for finding the “lost,” which of course first requires knowing who is in and who is out, which of course ends up using similar terminology like exclusivism, inclusivism, pluralism, and universalism — but not what we’re talking about today. I will cover “missions” soon in an upcoming post.

Scriptures often quoted to support Eternal Conscious Torment/Infernalism include: Isa. 66.24, Dan. 12.2, Matt. 5.22, 29-30, 7.13, 10.28, 13.38-42, 49-50, 25.31-46, Mark 9.43-45, Luke 12.5, 16.19-26, 2 Thess. 1.5-10.

Scriptures often quoted to support Annihilationism include: Matt. 10.28, 19.29-30, 25.46, John 3.16, 3.36, 4.14, 5.24, 6.40-68, 10.28, Rom. 5.21.

Scriptures often quoted to support Purgatory include: John 3.19-21, 1 Cor. 3.10-15, Heb. 12.14, Rev. 21.27

Proponents of this view often point to examples of Jesus’ provocative use of hyperbole (like Matt. 5.29, Matt 19.24, Luke 14.26) before explaining the history behind the “hell” terms being used. See William Crockett’s chapter in Four Views on Hell. For a more technical analysis on how first through fourth century hell rhetoric was used in teaching and formation without the presumption of literal description, see Meghan Henning’s monograph Educating Early Christians through the Rhetoric of Hell: ‘Weeping and Gnashing of Teeth’ as ‘Paideia’ in Matthew and the Early Church. You can read the first chapter here, and you can listen to her OnScript interview with brad Jersak here.

Scriptures often quoted to support Ultimate Reconciliation include: Luke 15, John 3.16-21, 6, 12.32, 12.44-50, 17.1-3, Acts 3.21, Rom. 5.18, 11.32, 1 Cor. 5.5, 15.22-28, 2 Cor. 5.19, Php. 2.9-11, 1 Tim. 2.4, Titus 2.11, Heb 2.9, 1 John 2.2, 2 Peter 3.9.

See the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon, 982-83. Two adjacent Hebrew terms are abaddon used only in 6 times in Wisdom Literature, describing a place of ruin within sheol for the lost or ruined dead (BDB 2) and shachat, meaning pit or cavern, used 23 times only in Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jonah (BDB 1001).

See Bauer-Danker Lexicon, 19.

See Bauer-Danker Lexicon, 991.

See Bauer-Danker Lexicon, 190-91.

The Septuagint (Greek version of the Old Testament) was likely translated slowly in sections in the third and second centuries BCE. Meghan Henning thinks that hades and gehenna had become closer in meaning by the late first century when the gospels were being written; see her book Educating Early Christians Through the Rhetoric of Hell, or for a cheaper option, you can listen to her interview with Brad Jersak on OnScript.

We also need to release the expectation that any usage of a word in scripture equals a full encyclopedia entry of meaning — there is no place in scripture where the writer thought “you know I should interrupt my reason for writing so I can define my usage of this word here against its other various meanings so that audiences two thousand years later can know for sure what I mean by it right now in this sentence.” Another mistake to avoid is “illegitimate totality transfer,” which is when an interpreter imports all the possible meanings from the semantic range of a word into one particular use of the word. Instead, we should remember that a word with a wide range of meaning can have one meaning in one sentence and a different meaning in another.

It’s important to remember that the more information a communicator assumes their audience already has in common with them, the fewer explanations and background material will be included in the discourse. We have to work harder to understand ancient texts and vocabulary since we don’t share the same cultural background assumptions as the original intended audiences of the biblical texts.

The adjective aionios is derived from the noun aion, meaning an age, a space of time, perpetuity, or an era.