REstory 18: Apocryphal Apocalypses and Pedagogy of Punishment

How learning about ancient literature and rhetoric makes “hell” make sense

I love alien and outer space movies. I watched a lot of X-Files in high school with my dad, and some of my favorite movies are Super 8, Arrival, and Interstellar. Most of the time when we engage narratives in media or art, we already have expectations about the genre before we even open the book or push play on the remote. For example, I know that the Apollo 13 movie is based on a true story, but that the 2021/24 Dune movies are based on Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel (because I had already read it).1

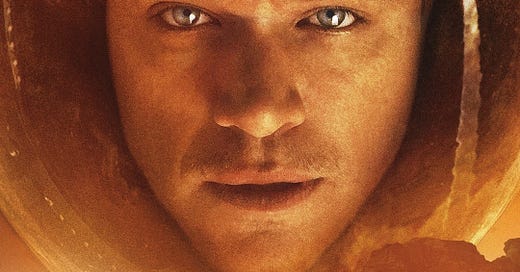

But sometimes writers or creatives surprise us by challenging our expectations, or other times we come to a story with the wrong expectations. When I first watched the 2015 film The Martian, I kept having to remind myself over and over, “this isn’t real—this didn’t really happen—nobody’s really been to Mars.” Because of the highly detailed portrayal of scientific realism for most of the movie, and because I hadn’t read the 2011 Andy Weir novel it’s adapted from, it felt really real—even as the logical part of my brain knew it wasn't.

This is a lot like unlearning and relearning about “hell”—many folks have to readjust what has felt real for a long time.

What many people who were taught that “hell” was literal haven’t heard is that “Netherworld tours” was a well-known genre in the ancient world.2 Richard Bauckham begins his book The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses by summarizing the common features of “descents to the underworld” from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Iran, Greece, and Rome. Ranging from 7th century BCE through the first few centuries CE, these tales and stories were sometimes used to explain the cycle of the seasons, to curate the legacy of a famous deceased person, to describe the fate of the dead, to teach the difference between good and bad behavior, to give a visitor a message about justice and ethics to take back to the living, or to rescue someone who had recently died.3

These types of stories were so common that writers, speakers, and teachers could reliably assume that their audience was familiar with the trope (and could then either conform to the regular structure of the trope or subvert or parody those expectations).4

This is true for us too—familiar tropes are all around us. You already have a set of expectations if your friend says “A preacher, a cowboy, and a lawyer walk into a bar…” Most of us can anticipate the storyline “city girl reconnects with hometown hunk while visiting for the holidays” that’s found in a Hallmark movie—whether we’ve watched very many or not—because it’s such a well-known motif. When your friend starts a tale with “It was a dark and stormy night,” you already have some guesses as to what the story could be like. None of these narratives have to be rooted in actual, historical experiences of daily life in this space-time universe for the stories to deliver their intended experience for the audience.

Another example a little closer to our topic of the afterlife are political cartoons with Peter standing on clouds in front of pearly gates, either welcoming or rejecting some recently deceased public figure. You already know that readers don't have to claim the Christian faith or literally believe in Peter or Heaven or God to have precisely predictable reactions to the message of the cartoon because everybody already knows the trope.

“Hell” is like this. Many biblical passages that have been used to support literal infernalism (or ECT = eternal conscious torment) can find a more appropriate home interpreted against a background of how various rhetorical tropes were being used at the time.

The Rich Man and Lazarus

One significant example is the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus found in Luke 16.19-31 (using the Greek word Hades). But actually the first thing that needs to be said is that this passage is a parable. We already know that parables are provocative stories meant to challenge or subvert the assumptions of the listener—parables are not reporting literal details of historical realities, and we know this most of the time.

Nobody is trying to figure out the name of the actual woman who lost her one coin or the village where the prodigal sons lived with their father or at whose delayed wedding half the bridesmaids fell asleep or the name of the actual farmer who sowed his seed over four really different kinds of soil—and it almost feels silly to point this out.

To attempt to get actual details of the geography of afterlife locations from a parable is to profoundly miss the point—not only of how the parable genre works, but also the theological or ethical subversion intentionally provoked by the parable.5

Back to the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus. The ancient audience hearing this parable (who then passed it on until Luke eventually writes it down) would have been familiar with other similar tropes of a visitor to the underworld who witnesses an ethical reversal of wealth and poverty in the afterlife and is concerned with reporting this back to the living.

One example is the Egyptian story of Setme and Si-Osiris (which you can find here), named for a father and son who observe two funerals—one of a rich man and one of a poor man—and then take a tour of the underworld where they see the reversal of those men’s fortunes.

According to Bauckham, there are at least seven Jewish adaptations of the Setme tale (you can find one here); scholars debate the proximity of the comparisons between the Rich Man and Lazarus and these other netherworld reversal stories.

Another similar example can be found in Cataplus, a satire by Lucian (from the second century AD—you can read a translation here).

The Sumerian poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld contains scenes revealing the fate of a dead character reported back to the living (you can read about it here).

The Book of Jannes and Jambres is a story (only fragments remain) describing one brother who dies while the other lives (you can access it here). After his death, Jannes attempts to send a message to persuade Jambres to change his life for the better, or else he’ll experience the same fiery heat and dark sadness as Jannes.

This is just a small sampling of the most relevant ancient tales describing a wealth-and-poverty or ethical reversal reported from an underworld visit that come closest to our parable. The point is that when we access ancient testimony (Luke’s writing about Jesus’ speaking), we need to expect the original audiences would have the average assumptions about genre and rhetoric that people held back then (instead of inserting our own).

Only then can we see how a main point of the Rich Man and Lazarus is that this parable deliberately subverts common features of that motif and turns the whole trope on its head. When we let Jesus’ parable do its work in its own context, we can see how Abraham’s refusal to grant the postmortem message back to the Rich Man’s brothers provocatively declares that apocalyptic revelations from the realm of the dead don’t work—the Torah and the Prophets have already said everything that can be said about God’s concern over the inexcusable injustice of economic disparity between the rich and the poor—they won’t even change if someone rises from the dead.6

The Sheep and the Goats

Another parable whose interpretation has been used to support literal infernalism (or ECT = eternal conscious torment) is the Sheep and the Goats found in Matthew 25.31-46.7 Some have assumed the story is about who goes to heaven or “hell.” Others say that the parable serves primarily to emphasize that what really matters at the final judgment will be what kind of care we have shown to “the least of these:” giving food to the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, welcoming strangers, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, and visiting the imprisoned.8

And while I think all of us should follow this list of others-centered care and compassion (all the time!), Matthew’s provocative goal is much larger (though it includes this point). Thomas Long widens the frame and shows how we need to see this parable as the climax of Matthew’s Jesus—a Jewish wisdom teacher with five grand discourses, portrayed throughout this gospel as the new Moses.9 This story is the crowning finale at the end of the fifth and final major discourse in Matthew. This last teaching from the lips of Matthew’s Jesus before the Passion should be read as coherent along the trajectory of all the discourses in this gospel that emphasize transformational discipleship into the Kingdom of Heaven (on Earth), beginning back with the Sermon on the Mount in chapters 5-6-7.

More specifically, the sheep in the story, called “the righteous/just” in v. 37 should be understood to be those who have been saying yes to the training-for-transformation Jesus has been offering all along throughout the teaching discourses in the gospel of Matthew. Like the Rich Man and Lazarus from Luke, the Sheep and the Goats also needs to be interpreted against the cultural and literary background that gives us clues to common stories and standardized tropes that a first century audience could already be familiar with—there were texts and traditions and tales at the time that gave lists of public ethics of compassion and the rewards that were prepared for those who do them.10

Paying attention to similar texts and tropes helps us see that what sets Jesus’ story of the Sheep and the Goats apart from others like it is the provocative detail that neither the sheep nor the goats seem to have a clue about how they got into their group. Neither group seems to know how much (or how little) they have already been demonstrating compassion to those Jesus cares about. The list of compassionate actions still matters very much (it’s repeated four times—giving food to the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, welcoming strangers, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, visiting the imprisoned). But when we remember Matthew’s larger goals, we see that the twist on the trope is making a primary point about transformation: these people are bearing this Jesus–fruit in their lives almost without thinking about it, because it is who they have become.

At this point, for folks who have heard for years that this story is about knowing who goes to “hell” or to heaven, that earlier interpretation will probably still feel real for awhile, because that’s what they’ve been taught—maybe even for a very long time after learning a better interpretation.

In our Bibles, it’s arguably Matthew who leans the most on the genre of “descents to the underworld.” Meghan Henning shows how Matthew appropriates the most phrases, imagery, and vocabulary from “netherworld tours,” a common trope that was used especially for teaching ethics at that time, in that part of the world.11

Ancient cultures around the Mediterranean had sophisticated and deliberate theories about basic education (enkyklos paideia) and teaching for wisdom (paranesis); training and formation (paideia) was an important category of rhetoric. Visually evocative language (ekphrasis) could be used when a teacher, acting as a tour guide, describes a place or experience so that students can see it in their minds as if it were before their eyes (periegesis). Using explicit or vivid vocabulary (enargeia) was applauded since it effectively engages the emotions of the audience and could provoke an ethical response.

For example, in a netherworld tour text, enargeia could include the “spectacle of punishment” when a character’s wickedness or selfishness led to corresponding penalties in Hades, like the rich being turned into donkeys to carry the burdens of the poor or different colored bruises on the bodies of the dead left by different vices or unending tasks like fetching water that never fills up. The provocative language about underworld punishments in the afterlife was pedagogical—it was a common teaching strategy to instruct the living how (not to) live.12

We need to interpret “hellish” rhetoric from Jesus more appropriately—within the context of ancient literary culture and common rhetorical practice.

For example, when Jesus says in Matthew 5, “If your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to go into Gehenna,” there is a lot going on here. Matthew’s Jesus knows that provocative punishment vocabulary is a common pedagogical strategy to engage the emotions of the audience and persuade them towards a certain ethical direction.13

Additionally, Jesus is offering a weirdly literal hyperbole here. When we pay close attention to this provocative overstatement in context, we realize how the statement turns on the word “if.” His statement is literal, but Jesus is not advocating self-mutilation because it turns out that it’s never our hands or our eyes that cause us to stumble.14 Our stumbling and our sin don’t begin in our body parts but in the desires of our hearts, which Jesus is offering to transform.

Do we really want to construct our ideas about a literal “hell” from passages like this? Doesn’t that seem like missing the point?

This kind of threatening pedagogy from the ancient world feels inappropriate to many of us today. Yes, we could motivate people by using fear or threat of violence, but should we? Isn’t it better to respect the dignity of others with nonviolent forms of persuasion? Especially if “Gehenna” is hyperbolic imagery based on destruction in the Valley of Hinnom? Especially if underworld tropes in scripture are included often to parody or subvert the expected usage at the time? Communication for persuasion is highly specific to the culture in which it’s found.15

Pastoral integrity requires handling biblical texts that contain apocalyptic imagery with extreme care that includes explaining unfamiliar ancient genres, lest we make converts who turn out to be “sons of hell” worse than us.16

Before I close, I want to point out that although Jesus does borrow phrases and imagery from “the spectacle of punishment” commonly found in “descents to the underworld,” in Matthew especially they are found within a larger context that we might miss—the Kingdom of Heaven. Contrary to popular assumptions, the phrase “heaven and hell” is found nowhere in scripture; instead the phrase “Heaven and Earth” is found over 150 times. And it is Matthew’s Jesus who gives us the vision of the “Kingdom of Heaven.”17

For first century audiences, “heaven” or “heavens” could mean skies or the dimension where God is—but not necessarily far away; it can be close by—and it’s not just after we die. Matthew uses heaven language several ways. “Heaven and earth” can be a merism (using opposites to indicate a totality that includes everything in between), so “heaven and earth” can be a phrase that means “the whole cosmos” or the entirety of what God has made.18

But Matthew also uses the phrase “kingdom of heaven” to show a contrast or rupture between heaven and earth—between the ruling realms of earth that have not given their allegiance to God’s realm—but it’s a contrast that hopes in the eventual reintegration of heaven and earth.

We know from other passages like Revelation 21, that the vision of the end is a new beginning where heaven comes down to earth and the two become one.

The Kingdom of Heaven was always Matthew’s larger point.

Jesus invites listeners to reject the flimsy, faddish, fraudulent kingdoms around us competing for our allegiance and affection and instead apprentice ourselves to him and start living into the Kingdom of Heaven right now.

It’s challenging to deconstruct fear-based myths we’ve been taught as true—right? Speaking of aliens, when I was in elementary school, I was told that mass hysteria was caused by a radio broadcast on October 31, 1938. As the story goes, when Orson Welles performed a dramatic reading of H. G. Wells’ science fiction novel The War of the Worlds with the voice tone of a news broadcast, listeners who missed the introduction thought they were hearing an announcement of an actual alien invasion, and widespread public panic ensued.

Unfortunately, this proves not to be true. The evidence points instead toward a few accounts exaggerated into a much larger story by newspaper media companies that were losing audiences to radio. The myth became sensationalized in the following decades by several key players, and the legend of this “apocryphal apocalypse” continues to be retold today.19 Sometimes our inherited expectations are wrong and need to be adjusted.

Without understanding the cultural context, many churches have interpreted Jesus’s “hell” language as weapons of mass destruction instead of tools of mass instruction. Whenever “hell” is used to pressure or motivate faith or behavior (so you better believe the right things about Jesus OR you better try to never sin OR you better take communion exactly right OR ELSE…) then it might take a long time to unlearn. It might take years for the anticipatory joy of God’s promise to heal the whole cosmos to replace the effects of years of fear-based persuasion. God’s project is to make all things new, which is the subject of the next post. God wants us to be partners in bringing heaven to earth, and there are plenty of folks on this journey to keep us company.20

© 2025 Ladye Rachel Howell. All Rights Reserved.

We became so convinced that reading science fiction was an invaluable tool for expanding the imagination and empathy needed for cross-cultural work that my husband wrote a journal article about it.

Some “netherworld tours” were not descents but ascents to visit the dead in the upper atmosphere, and others were pilgrimages to visit the dead in the west (where the sun goes down). Some scholars suggest that the genre of the “netherworld tour” should be considered as a subset of the larger category of “cosmic tours.” See Richard Bauckham, The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses, ch. 1.

Bauckham also covers redaction and reception of some of these apocalyptic narratives through the patristic and medieval periods.

A partial list of texts that include visits to the underworld in Bauckham’s survey (p. XIII-44) follows here. Outside of Jewish and Christian traditions, notable texts are Enlil and Ninlil, Gilgamesh Enkidu and the Netherworld, Epic of Gilgamesh, the Book of What is in the Other World, the Book of Gates, Setme and Si-Osiris, the Arda Viraz Namag, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Menippus, Peri physeos, Philopsuedes, Cataplus, The Frogs, and Axiochus. Within Jewish and Christian communities, some of the texts included are 1 Enoch, Apocalypse of Elijah, 2 Enoch, the Apocalypse of Zephaniah, 2 Baruch, 4 Ezra, the Apocalypse of Abraham, 3 Baruch, the Greek Apocalypse of Ezra, the Latin Vision of Ezra, the Apocalypse of Sedrach, the Question of Ezra, the Apocalypse of the Seven Heavens, the Ascension of Isaiah, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Apocalypse of Paul, the four Apocalypses of the Virgin Mary, the Coptic apocryphal Apocalypse of John, the Mysteries of John the Apostle, the Greek apocryphal Apocalypse of John, the Questions of Bartholomew, the Ethiopic Apocalypse of Baruch, the Apocalypse of Gorgoios, the Hebrew Apocalypse of Elijah, and the Gedulat Moshe.

This video of a sermon makes precisely this category mistake and has fundamentally missed the point. Describing what a parable is, Thomas Long quotes both Clarence Jordan (“When Jesus delivered his parables, he lit a stick of dynamite and covered it with a story”) and Sallie McFague (“If the parable works, the spectators become participants…. the secure, the familiar everydayness of the story of their own lives has been torn apart; they have seen another story.”) See Thomas G. Long, Proclaiming the Parables: Preaching and Teaching the Kingdom of God, xi-10.

See Bauckham, ch 4. In our own time, movies like It’s a Wonderful Life and books like Dickens’ A Christmas Carol are versions of this trope wherein a character receives an angelic or otherworldly view of their own life and makes significant character changes. These stories are much more optimistic about capacity for charitable change than Jesus’ parable about The Rich Man and Lazarus; one wonders about our need to soothe ourselves with ethical optimism around consumer holidays.

Long, 239-40, calls The Sheep and the Goats a “parabolic narrative,” noting that many scholars acknowledge that it is not strictly a parable since it lacks the narrative setting features; at the same time many scholars note that “there is something about the rhetorical character of this text that invites readers to receive it as one of the parables.”

Another common interpretation emphasizes that when we care for the poor we are caring for Jesus, which I don’t deny. Many interpreters through the years have also focused on the identity of “all the nations” in v. 32 (if that includes Israel or is just the Gentiles), or the identity of “the least of these my brothers” in v. 40 (is this a narrower critique of lack of care of travelling apostles). See Long, 238-43.

Long, 238-43.

Long quotes from 2 Enoch 9.1 to demonstrate this; you can access a translation of the text here. As examples of “misfortune lists” that correspond to description of the “least of these” in Matthew 25, Hultgren 309-330 includes Epictetus Dis 3.3.17-18, 3.10.0, 3.24.29, 4.6.23, T. Jac 2.23, T. Jos. 1.5-7, or Isa 58.6-7 or Zech 7.9-10. See Arland J. Hultgren, The Parables of Jesus: A Commentary, 309-330. Additionally, this separation of people into two groups based on their behavior during life, where the unjust are directed “down” and to the left and the just are directed “up” and to the right is also found in Plato’s Republic (Book 10.614-616).

See Meghan Henning, Weeping and Gnashing of Teeth: The Pedagogical Function of Hell in Matthew and the Early Church, 171. Bauckham, 79-80, also traces the development of “hell tours” within the tradition of Jewish apocalyptic literature.

See Henning, ch. 3.

The three references to Gehenna from Matthew 5 in the Sermon on the Mount and the three corresponding usages in Mark account for half of the twelve occurrences of the word in the New Testament. Scholars debate the value of distinguishing between the terms Hades and Gehenna. Meghan Henning thinks that the terms had grown closer by the time of Matthew's writing, which might show signs of slippage or interchangeability. Just as compelling is the possibility that Jesus is subverting the phrases his audience might expect to hear by injecting the term Gehenna (from Israel's self destruction in Jeremiah 6-7, which makes it personal) for Hades (the name of the underworld in Greek culture).

Additionally, there are so many layers to this testimony. Jesus’ words in Matthew 5 require an understanding of how his community had discerned their ethics from Torah for generations, because he was subverting and transcending those expectations. Part of my point is that understanding how many layers of mediation exist between us and Jesus's actual teaching moments should bring delightful humility. Teachers and preachers need to lead their communities through these layers of context in order to not cause harm.

Henning, 186, notes that both Philo and Josephus discuss dismemberment as a strategy for sin.

See Wayne A. Meeks, “Apocaplytic Discourse and Strategies of Goodness,” in The Journal of Religion, July 2000, 80:3, 461-475.

Matthew 23.13-15

Other evangelists use the phrase “the Kingdom of God.” When I was a young adult serving in campus ministry, I was traveling with college students, and I heard a preacher at a conference yell from the pulpit “THE KINGDOM IS THE CHURCH” (over and over and over again). But the way Matthew is using basilea (kingdom) isn’t synonymous with church (the group of people that were eventually known as the church are the ekklesia (the called out / gathered ones). Jesus often uses verbs of entrance or inheritance when he talks about the kingdom he’s describing; kingdom is more like a place—the realm where God reigns—where what God wants done is done.

See Jonathan T. Pennington, Heaven and Earth in the Gospel of Matthew.

See War of the Worlds to Social Media: Mediated Communication in Times of Crisis and the Slate.com article “The Myth of the War of the Worlds Panic.”

See Trauma Informed Evangelism, by Elaine Heath and Charles Kiser. See also Dan Koch’s Spiritual Harm and Abuse Scale.