REstory 17: Drinking the Kool-Aid as We Cross the Rubicon

Why researching “hell” requires learning how history becomes the loaded metaphors of future generations.

This is the third post in our miniseries on our inherited doctrines about hell — be sure to reread the first post and the second post for important definitions and if you need a refresher. Also, doctrines about hell are very interconnected to what people have been taught about the gospel or theories of atonement, so that miniseries is relevant to this one too!

Some folks have gotten the impression from church that taking the Bible “literally” is the only way to have “a high view of scripture,” though many are aware that certain sections like parables and poetry could be exceptions, because those genres work differently. But idioms, metaphors, and other examples of figurative language are everywhere — in our lives and in the Bible — and not just in parables and poetry. In the last post we discussed how Amelia Bedelia is an (annoying?) example of an adult character who gets everything wrong and causes chaos for everyone around her because of her ignorance of how complex figurative language works.

Anytime we read ancient scripture, we are both time-traveling and doing cross-cultural communication, which is a great opportunity for humility. Cross-cultural communication can be fun, but it can also be hard work that requires a lot of endurance. It can be extra tricky when learning idioms and metaphors, especially when navigating the nuances of phrases that are loaded with history, and even more when the details have faded from awareness, either due to overfamiliarity or distance. This is a crucial piece in learning how the concept of “hell” developed over time. So yes, this is hard work, but we also already do this in everyday language — I’ll share a couple examples before returning to the topic of hell.

First, one example is the phrase “We’ve crossed the Rubicon.” All meaning is contextualized — if I’ve just crossed a small river while traveling in northern Italy, you might be able to interpret me literally. However, many will know that phrase often figuratively means something like, “We’ve passed the point of no return,” referencing a critical decision that will determine outcomes that can’t be undone.

The audience can be familiar with the idiomatic phrase even without knowing that the historical backdrop refers to when Julius Caesar, then a powerful governor of Gaul, led his army across the river Rubicon in January 49 BCE, effectively declaring war on Rome (which he eventually won).1 Interestingly, it turns out that the river crossing (with Caesar supposedly quipping “the die is cast”) may have been over-dramatized in the accounts of ancient historians, especially if the civil war had technically already begun (as some modern historians point out).2

Another example is the sentence “They drank the kool-aid.” If I’m describing a 4-year-old’s birthday party, you know I’m being specific and literal. But if I’m describing a dysfunctional organization where members are under the influence of a charismatic but corrupt leader and failing to question the wisdom of his decisions, you know that I’m using the phrase as a metaphor that alludes to groupthink, blind obedience, or potentially dangerous loyalty in a group peer pressure situation (even if no sugary fruit drinks are involved).

Some folks may know that the metaphor comes from a historical event: the group poisoning back in the 1970’s under the direction of cult leader Jim Jones, an American living in Guyana — hundreds died because he influenced them to drink poisoned beverages. But others will know the “groupthink” or “blind obedience” meaning of “they drank the Kool-Aid” even if they aren’t familiar with the backstory.

The additional irony is that “drinking the Kool-Aid” carries the metaphorical meaning even though many sources have pointed out that it was actually the Flavor-Aid brand that they drank laced with poison, not actually the brand Kool-Aid. That detail in the wording of the phrase is incorrect, but none of us can change that metaphor now — just 46 years after the event.3

My point is that over time events from history can become compressed into a word or phrase, and the further removed one is from the event, the more humility, curiosity, and learning is required to not twist or shift the details and the meanings of the texts or testimonies or traditions as we receive them.4 Additionally, it’s important to remember that different understandings can evolve in different groups or regions.

Which brings us back to Gehenna, one of the primary terms that needs to be studied to investigate where hell doctrines come from. The title of today’s post, “Drinking the Kool-Aid as we Cross the Rubicon,” is my way of reminding us of both the vast historical distance between us and the first century, and also to widen our expectations for layers of complexity around the multiple ways that concepts around the word Gehenna developed.

Direction(s) of the Development(s) of Gehenna.

First, we already discussed in the last post how the valley of Hinnom (Ge Hinnom) was a real place where (centuries before Jesus) the people of Judah adopted pagan worship and practiced child sacrifice under the leadership of Ahaz and again under his grandson Manasseh. His grandson Josiah “defiled” the space to prevent the people from engaging in those despicable practices again. Then messages through the prophet Jeremiah make it clear both that God abhors what they did there and also that the valley will become a place of slaughter when they’re invaded by the Babylonian empire.5

Jeremiah was a witness to that predicted devastation of Judah and Jerusalem. In two major waves, usually dated 597 BCE and 587 BCE, Babylon besieged, invaded, and eventually destroyed Jerusalem.6 Although the ways writers referred to Gehenna evolved over time, it’s important to firmly establish that the primary historical reference is the impending and actual destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon after decades of idolatry and wickedness from the times of Ahaz, Manasseh, Josiah, and Jeremiah. The people of God engaged in child sacrifice in the valley of Hinnom as part of their descent into imitating the worship practices of neighboring peoples.

God is horrified at the horror of their actions.

They will reap the violent consequences of their violence.

This is the historical reference for Gehenna that is being carried forward in the sorrowful communal memory of Jeremiah and the other immediate survivors of those invasions; it becomes a loaded reference or a theological shorthand that can be alluded to with a word or a phrase by those in the following generations. We need to both prioritize this devastating historical tragedy as the primary meaning and admit the meaning of the word/ phrase/ concept has assuredly shifted and expanded over time.

The passage of time is a significant factor, especially considering the writing and record-keeping technologies and practices available at the time — over 500 years pass after the sieges of Jerusalem by Babylon before Jesus comes on the scene.

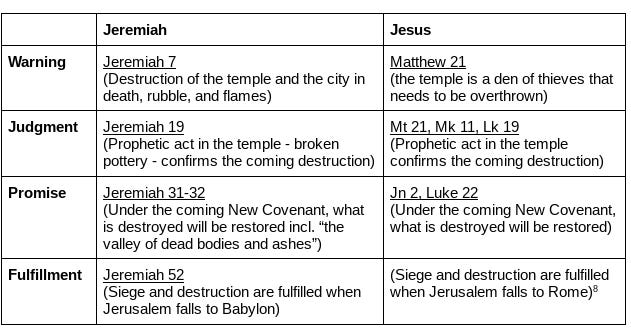

Theologian Brad Jersak sees a pattern from Jeremiah’s prophetic ministry that we can see imitated in the recorded ministry of Jesus: Warning — Judgment — Promise — Fulfillment:7

Two “Traditions”

Jersak describes two streams of thought. First, the chart above demonstrates the “Historic-Prophetic Tradition,” emphasizing that in this strain, “Jesus’ use of Gehenna intentionally references Jeremiah’s prophetic use of ‘Hinnom’ to represent imminent literal destruction. Jesus is recalling the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC as a warning of the impending fall of Jerusalem to Rome in AD 70.”8

However, during the intervening 500+ years, the use of Gehenna in religious discourse expanded among some groups to mean punishment by fire in the afterlife. Jersak traces passages from Apocryphal texts (such as 1 Enoch and 4 Ezra/2 Esdras), Rabbinic commentary in the Talmud, and then some voices from the early church whose interpretation of Gehenna evolved beyond Jeremiah’s agonized predictions of both devastation and healing — some in these groups began to embrace versions of infernalism.9 This stream could be called the “Apocalyptic-Infernalist Tradition” (to be distinguished from the “Historic-Prophetic Tradition”).

Side Note: In biblical studies, “Apocalyptic” does not mean cataclysmic destruction to end the world, but instead refers to a genre of writing that uses vivid, other-worldly imagery to describe the very real horrors going on currently in their own world. Based on the Greek word for unveiling or uncovering, the “apocalyptic” genre aims to “reveal” the high stakes implications of the violence and devastation in their own world. (Check out this Bible Project video on Apocalyptic literature, and for a much more detailed background, see John J Collins’s book Apocalyptic Imagination).

The “Apocalyptic-Infernalist Tradition” shows how the concept of Gehenna had expanded for some Jews and Christians in the first few centuries of this era. For some, the actual Valley of Hinnom and the events that happened there had already begun to take a backseat to vivid imagery of a valley of burning fire in the afterlife; this is seen clearly in the pseudepigraphical work 1 Enoch but also in others.10

The central question about Gehenna here is whether we can discern which tradition had influenced which first century audiences and how much and when — all of which is debated. (I’m including links in this detailed footnote to resources that describe and summarize the diversity and direction of views of Gehenna after the time of Jesus from the Talmudic rabbis.)11 Ideas became more entangled over time as “apocalyptic” writings (the genre that uses otherworldly imagery to describe real-world horrors) became fused with increasingly literalized “apocalyptic” predictions about the afterlife — and it often seems like the latter “apocalyptic” has overtaken the former.

But the testimony in the book of Jeremiah itself predicts a different trajectory for Gehenna — the descriptions of terrible consequences resulting from the horrific violence of the people (like in Jeremiah 7 and 19) are not the final word. In Jeremiah 31, the phrase “the days are surely coming” is repeated multiple times among hints of a “New Covenant,” culminating in a descriptive promise of the rebuilding of Jerusalem, including “the whole valley of the dead bodies and the ashes” that will be made holy to Yhwh.

Gehenna for Jeremiah is not final; “hell” is not the end.

In Jeremiah 32, God emphasizes a future healing of the land when “houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land,” and even provocatively tells Jeremiah to buy a field.

You’d think buying a field during a siege would be ridiculous. But as Babylon’s invasion is on the threshold because of Judah’s own self-destruction (which included child sacrifice in the valley of the Sons of Hinnom), God is promising through Jeremiah that they will be re-gathered, that their hearts will be healed, and that God will live among them, faithful to a forever covenant (Jer. 32.29-44).12

The book of Jeremiah holds both the horror of the people’s worst nightmares and also the hope of healing (which, sadly, that generation would never see). God is clear that child sacrifice that was happening in the Valley of Hinnom had not been commanded and “had never even entered my mind.” Brad Jersak encourages us to “note the irony and incongruence of the church using the very place where God became violently offended by the literal burning of children as our primary metaphor for a final and eternal burning of God’s wayward people in literal flames.”13

None of us reading this post were personally there when Caesar “crossed the Rubicon,” nor when the Jonestown cult “drank the Kool-aid,” but we live in a world where those phrases are part of the English language. People around us use the phrases whether they understand the background or not. Language is often loaded with history, and even then it shifts or becomes layered with expanded meaning over time (whether we like it or not).

In the next post we will return to Jesus, focusing especially on his words that we find in the gospel of Matthew. Today, however, we’ve focused on how learning the backstory of the very real Valley of Hinnom and the people’s ravage and ruin there helps us consider how referencing that history changed and shifted over several centuries before Jesus. We must wrestle with the portrait of God behind the hell doctrines we have inherited. Would the same God we read about in Jeremiah 7, who is brokenhearted and indignant at the violence of killing children by burning, also design eternal flames of torture for those who don’t follow his ways?

What kind of God does Jesus reveal to us?

© 2024 Ladye Rachel Howell. All rights reserved.

Check out this History.com video. Also, this episode is retold in Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars (Section XXXII is found on p.22).

Visit JSTOR for a review of Christian Meier’s book Caesar by Badian in Gnomon; the relevant section is on p.30.

Most of us use the word “traditions” to mean repeated rituals in our community — like the way your family had traditions (foods, candles, songs) for a certain holiday that might be the same or different from a family in another country. Or how one church might have the tradition on Ash Wednesday of marking a cross on your forehead, but the church down the street didn’t. In biblical studies and theology, however, “traditions” means how ideas developed and spread through a community and across regions and generations.

Josiah’s actions to “defile” the shrines in the Valley of Hinnom (and multiple other sites of idolatry and violence) are found in 2 Kings 22; “defiling” a shrine by burning the equipment and the site and by covering it with human bones would make it unfit and unusable for a future worship shrine. The valley of the sons of Hinnom is also called Tophet — see 2 Chronicles 28.3 and 33.6, 2 Kings 23.10, and Jeremiah 7.27-34, 19.2-6 and 32.35. We also discussed in the previous post how there is no primary evidence for the often-circulated idea that first century Gehenna was a “smoldering garbage dump with unburied bodies.”

For the Siege of Jerusalem, see 2 Kings 24, 2 Kings 25, Jeremiah 39 texts, and this Britannica entry.

See Bradley Jersak’s book, Her Gates Will Never Be Shut: Hope, Hell, and the New Jerusalem. This chart is on p. 35.

Ibid. Again, remember that in this discussion, “tradition” does not mean patterns of rituals and practices repeatedly used in a community. Instead, in biblical scholarship, “tradition” refers to how information, story, and meaning was passed down through generations but naturally developed different variations in different regions or groups.

Remember from the previous post that “infernalism” is another name for the view that Hell is defined by “Eternal Conscious Torment.”

Chapter 90 of 1 Enoch is the one most often quoted. For an accessible introduction to “intertestamental literature” like 1 Enoch, see Matthias Henze’s book Mind the Gap: How the Jewish Writings between the Old ad New Testament Help Us Understand Jesus.

On p.41-52, Jersak demonstrates that although there is considerable diversity concerning Gehenna among the rabbinic writing in the Talmud (ca. 200 CE), he summarizes four notable themes: 1-Gehenna becomes a metaphor for suffering in the afterlife; 2-Gehenna can have a time limit (usually one year); 3-Gehenna may have an exit; and 4-Gehenna can be a place of purification. He stresses that we shouldn’t read these views anachronistically back into the first century, since the Talmud gives a picture of the diversity and direction of views that had developed 150+ years after Jesus’ teaching. Jersak additionally emphasizes that when researching what first century audiences might have thought when they heard the word Gehenna, it’s important to remember that Jesus as a rabbi regularly engaged his audiences with discourse and dialogue that challenged their assumed categories and concepts.

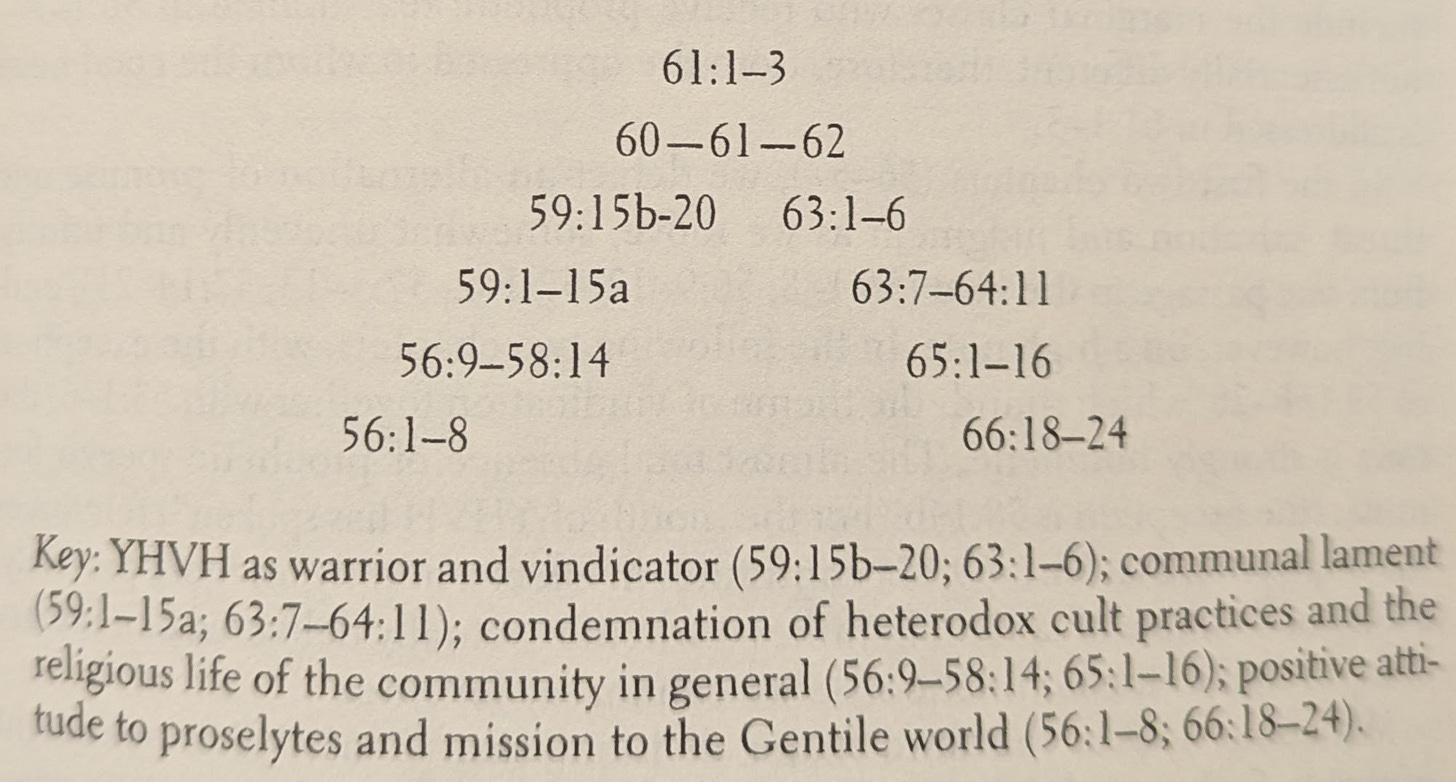

The final lines of Isaiah are also sometimes brought into discussions of the development of doctrines of hell. In Isaiah 66, there have already been references to gathering the nations and a future new heaven and new earth, but then the final line reads, “And they shall go out and look at the dead bodies of the people who have rebelled against me; for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh.” This is not a mic drop for the Infernalist position; instead this is an example where missing the structure of an ancient text can cause a reader to misunderstand possible meaning. Without denying the dreadful imagery in those ending lines, many scholars see the literary structure (sometimes called a chiasm, or cone, or ring) of Third Isaiah (Isaiah 56-66) as showcasing chapters 60-61-62 as the center of gravity within the work. This should affect whether or not we give Isaiah 66.24 the weight of “the last word” in the book and help us wrestle with where the main emphasis lies in Isaiah 56-66. See structure examples below:

Jersak, Her Gates Will Never Be Shut, p. 65.

There is a high probability that your readers and listeners on this Substack who have not already done so will find themselves surprisingly and joyfully on the other side of the the rubicon that divides a theology which worships a dark and angry god of infernalism and torture from that LOVE which holds the cosmos in an ever expanding divine dance.

You are doing essential work which has to begin at this very point.